This is a record of the how and why behind my first attempt at supporting students to write high quality prac reports. This post has been prompted by: Ben Rogers’ interesting post on the same topic, the fact that I’ve been meaning to write about this for ages, and the fact that it’s now time to re-design this process for the coming school year, retaining the wheat and discarding the chaff (hence the 1.0 in the title). If you have any suggestions regarding ways to improve or refine the process outlined below, I’d love to hear them via the comments, twitter, or email.

This post is split into a few sections. It starts off talking about how I started trying to use rubrics and felt they weren’t achieving what I wanted them to. It then goes on to how I scaffolded student science report writing using a highly structured example and sentence starters. Then discusses in detail assessment processes, including a peer-marking component. In addition to this, assessment of surface and deep structure are discussed separately. It concludes with my ideas for the coming year, as well as a list of questions that I still have and that I’m trying to answer.

This was meant to be the sharing of a few ideas, but it’s ended up being a massive and very detailed post. Hopefully the level of detail is helpful to people, and hopefully it opens up some edifying discussions.

The quest for the perfect rubric

I did my teacher training at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education and in our unit Assessment for Teaching there was a massive emphasis on writing quality rubrics and using them to scaffold student learning. We learnt that assessments need to be: Appropriate, assessing the right stuff; Adequate, enough data collected; Accurate, make sure the student wasn’t sleep deprived on the day;and Authentic (wasn’t done by mum and dad). All handy stuff.

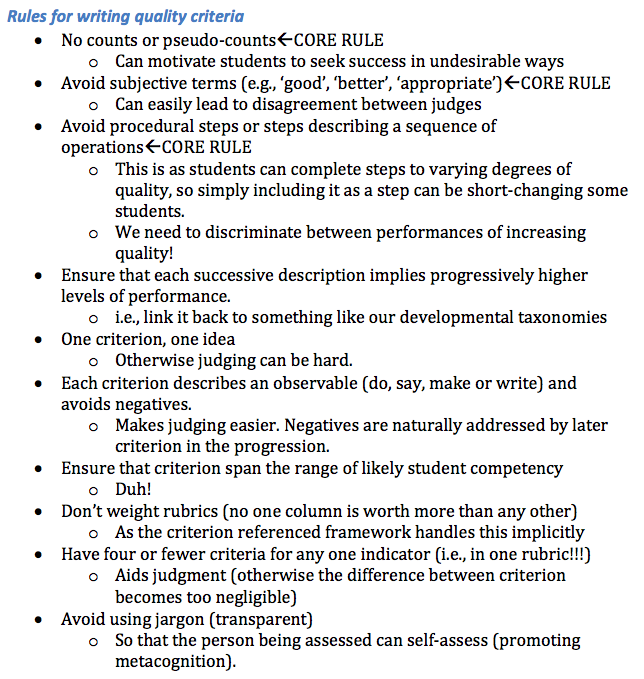

We also learnt that a rubric is made up of ‘indicative behaviours’ (the things at the bottom of the columns), and its associated ‘quality criteria’ (the little boxes up each column). We were taught that we should align the levels of our rubrics with those from a developmental taxonomy (e.g., SOLO, Dreyfus or Bloom/Krathwohl), and that the following rules should be followed when writing rubrics (screen shot from my notes from class).

And so, my fellow teachers and I left our initial teacher education training feeling like we had a really solid feel for what a good rubric was, how to write one, and how to use one.

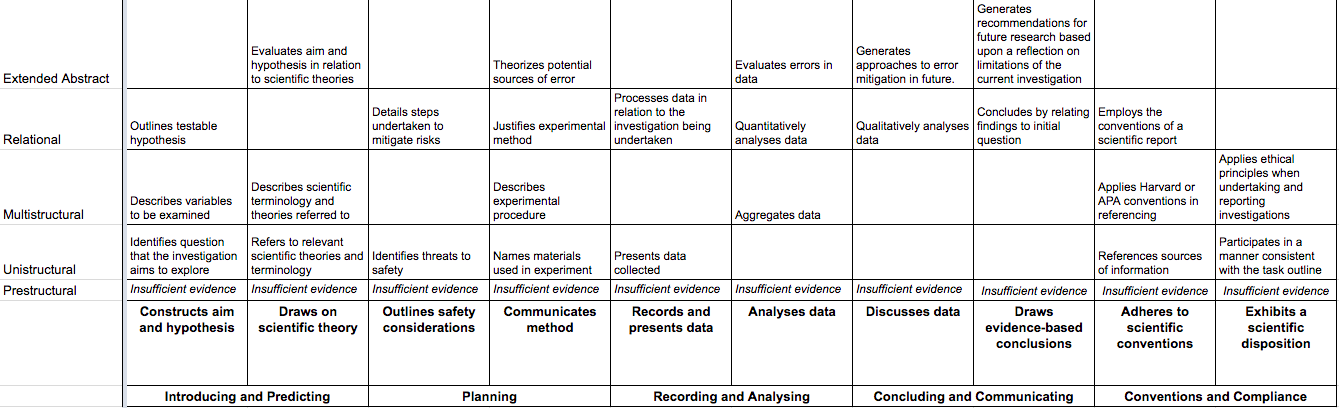

The effect of this was that, when the opportunity arose for me to scaffold and assess students’ science prac writing for the first time, my instinct was to start by writing a rubric. And boy did I spend a bunch of time on this. I spent literally hours pouring over other people’s rubrics and trying to construct the best science prac report rubric in-tha-wrld. Here’s what I came up with… (click to enlarge)

And so it was that I had scaled the great mountain of rubric and come out victorious. Or had I? I figured the next step was to borrow a few pracs from the previous years’ class and have a go at scoring them. This is where the problems really began. Here’s an indicative list

- It took ages to mark anything:There are 26 quality criteria (individual boxes with stuff in them) in this rubric, and hunting through a paper to try to work out whether a quality criteria was or wasn’t fulfilled was super time consuming.

- It caused me to have a narrow focus: I found that the impact of trying to work out if a criteria was or wasn’t fulfilled meant that I was reading more for tick boxes than for meaning, expression, and scientific accuracy. It moved me away from the ideas behind a students’ writing and towards this box ticking in a way that I really didn’t like.

- It didn’t provide a sufficient level of detail: I found that the quality criteria weren’t half as binary as I thought they’d be. Take for example ‘Describes experimental procedure’, well, every student did this to some degree, but some of them just didn’t make sense, and some of them were exquisitely composed, yet I’m only supposed to assign a 1 or a 0 to this criteria. This really doesn’t help anyone.

- It would be pretty unhelpful for students in the task completion phase: What the heck does ‘Evaluates errors in data’ mean if you’ve never done it before.

- It would be pretty unhelpful for students in the feedback phase: The idea is that if students are at one level of the rubric then they can simply look to the next level and say ‘ok, well, to improve my mark, I’m aiming to that next ‘square’ now’. But in reality this suffers the same problem as in the previous dot point.

So, it didn’t seem like this was going to be the best approach after all. Despite all my training I just couldn’t se a way to make this marking approach a time efficient and supportive way to scaffold and assess my students. There had to be a better way.

Note: Maybe it was just because my rubric sucked? Well, whilst doing the Assessment for Teaching course we were directed to the website ‘reliable rubrics’, created by my lecturer. Since I wrote my rubric they’ve created a rubric for exactly the same physics assignment that I was creating mine for (available here). To my eye it still suffers from all the same challenges.

Hmm…How about work samples?

Turns out I had just had a parallel experience from which I could draw some lessons. A couple of weeks before I had dived into this rubric writing rabbit warren I had finished writing my Masters thesis. This was pretty much the same task in that I had to synthesise a whole heap of ideas into a format that I was unfamiliar with in a way that I’d never done before. When I hit this rubric road block, I thought back to how I’d tackled this similar challenge and realised that what I’d done was: find examples of high quality theses, read them, make notes about what made them great, and translate this into my own context and writing. Maybe I could do this for my student too? This could be summarised as providing work samples to students.

Since this time I’ve come across others (such as Dylan Wiliam, see technique 1 here) that suggest the same approach. So, this is what I settled on. Unfortunately there weren’t any student work samples of a high enough quality that I could find, so I decided to write my own. And instead of simply giving students the work sample, I also wanted to deconstruct it for them in a way that they could easily pull out the key points. Here’s how I did it (I did for all sections of the prac report, but I’ll just share the intro here).

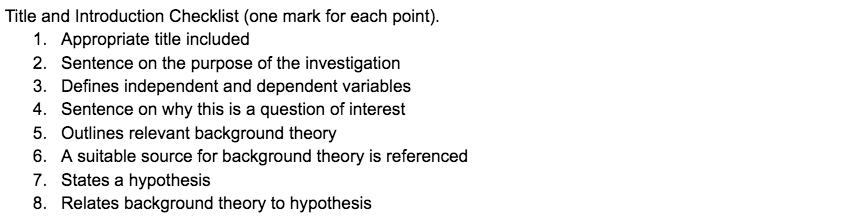

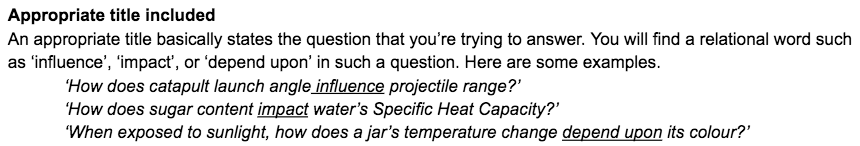

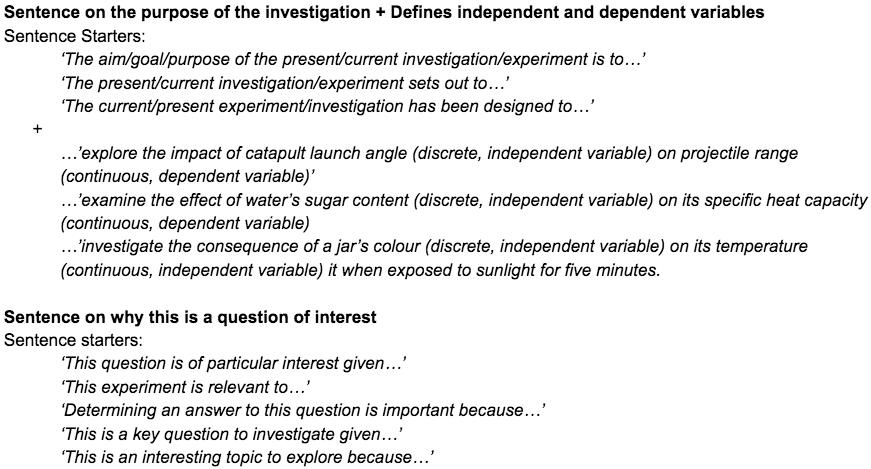

First this was to list the components that an introduction should include:

Then I broke each step down, explaining its purpose and giving examples. I also tried to explicitly point out the kind of language that I knew students would find it helpful to use (There’s probably a better word than ‘relational’ here, but hey, I’m not an English teacher)

For some of the sections I also provided sentence starters. Here are examples for points 2 and 3 from the above checklist.

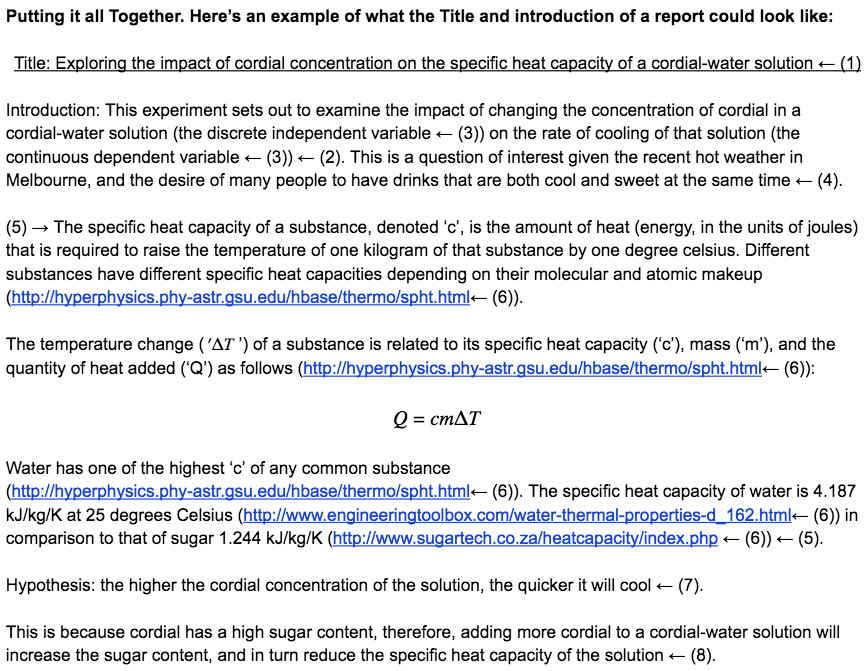

And finally, I put it all together in an example, clearly highlighting exactly how each of the bits fit together.

References are in a weird format because I was doing one step at a time and only scaffolded referencing after we’d had all the basics down.

So, how did the students find this as a scaffold? Bloody brilliant! Here’s a heap of student work samples from their first crack at the report. I’ve bolded the sentence starters that they used, and I’ve underlined the ones in which the students varied a bit from the exact sentence starters that I provided (Keep in mind that around 50% of my class are English language learners, I think that for them this approach was particularly helpful).

The aim of the present investigation is to examine the effect of voltage on current flows in the electric circuit. The dependent variable in this investigation is the current which is dependent on the voltage ( independent variable ). This is an interesting topic to explore because the practice report is based on the voltage and current in the circuit.

The purpose of this experiment was to construct a simple circuit that contains an Ohmic resistor (resistor value may vary with each groups, 10 Ohms, 50 Ohms, 100 Ohms) to explore the impact on the current that flows through the circuit when different voltages are applied. This experiment is relevant to the topic that we are learning in class. By doing this experiment, we can get a better understanding of the relationship between voltage and current, whilst also applying an Ohmic resistor in the circuit.

The current investigation has been designed to explore whether the circuit’s current is affected when the voltage of the circuit is altered. The independent variable of the experiment is the voltage applied to the circuit, while the dependent variable is the current of the circuit. This experiment is of particular interest because it shows how voltage and current go hand in hand with each other when there’s a ohmic resistor involved. This is especially important because it gives a greater understanding of how electrical circuits work which can be of great use in daily life as they are practically found everywhere.

The experiment aims to investigate the relationship between potential difference, current and resistance, and examine how different voltages applied affect the total current, on a series circuit. This is a topic of interest given, the potential difference, current and resistance are incorporated in common appliances used everyday and therefore the findings, will help develop a deeper understanding of these concepts.

The purpose of the present investigation is to explore the impact of the voltages (the discrete independent variable) on the current (the continuous dependent variable) in the built circuit. Determining an answer to this question is important because this practical helps students to create their own circuit and find out the disproportion between the predicted and actual current depending on the different voltages.

The experiment sets out to investigate the impact of variable voltage on current that passed through Ohmic devices.This is a key question to investigate because the result of this experiment will stand as a solid and practical prove for the Ohmic Law V=IR, which is one of the most fundamental laws in our current field of study of electrical physic.

The purpose of the present investigation is to examine the impact of changing the resistance (the independent variable) on the current and the voltage of the circuit (the dependent variable). This experiment is of particular interest given because it helps us understands Ohm’s law in action and determine the circuit with resistors.

This one is classic! The student didn’t get that the numbers that I provided were for student reference only, so they included them in their report!

(1/2) The purpose of this current investigation is to explore the effects voltage(which is the independent variable) has on a current(which is the dependent variable) in the circuit.(4) this particular investigation is important because it is related to how voltage and current relate to each other and how they affect each other, also relating to Ohm’s Law(V=IR).(5)

Another thing worth noting was that I spaced out these tasks throughout the year. The first task I got students to do was to perform an experiment that I’d designed and to write only the intro and methodology. Second up I got them to do another experiment and write up the intro, methodology, and results. Finally, I ‘supported’ them each to design their own experiments (though I did this very badly, will improve that this year), and got them to write up all elements of their prac report from start to finish. This also meant I could progressively create the guide, which was obviously a pretty time consuming task.

How the heck do I mark these things?

Thinking about the assessment of these reports in detail, I realised there were two levels at which I could give scaffolding and feedback, surface and deep structure. Surface structure includes stuff like: Does it sound science-y?; have they included all the steps?; etc. Deep structure is: Does their hypothesis make sense?; Have they referred to the correct scientific theories; etc. And it simply doesn’t make sense to me to mark each of these structural levels in the same way. Furthermore, we have to give feedback on both levels. If we just give deep structure feedback then students will have good ideas but won’t be able to express them well or in a way that accords with the conventions of a scientific report. If we just give surface structure feedback then they’ll sound professional but they won’t really be communicating ideas of any value. So let’s look at each in turn.

Marking surface structure

Surface structure tricks people. It’s tricks novice students when they’re trying to categorise physics problems –Oh, these problems are all about cars and these ones are about planets , vs. These problems are all about conservation of momentum and these ones conservation of energy, (see Chi, Feltovich and Glaser, (1981)) and they’re what tricks inexperienced teachers when they’re marking student reports (Which Ben Rogers refers to in his aforementioned blog post).

Frankly, I can’t think of anything more boring than marking surface structure. I simply don’t want to go through a prac report and go through a tick list of whether or not students have or haven’t defined their dependent and independent variables. Further to that, as I stated above in my rubric-critique, I don’t feel like I can mark surface and deep structure at the same time. If I’m ticking boxes I can’t follow the thread of a students’ argument at the same time, and vice versa. So to mark surface and deep structure would require me to go through each assignment twice. Besides, anyone can mark surface structure.

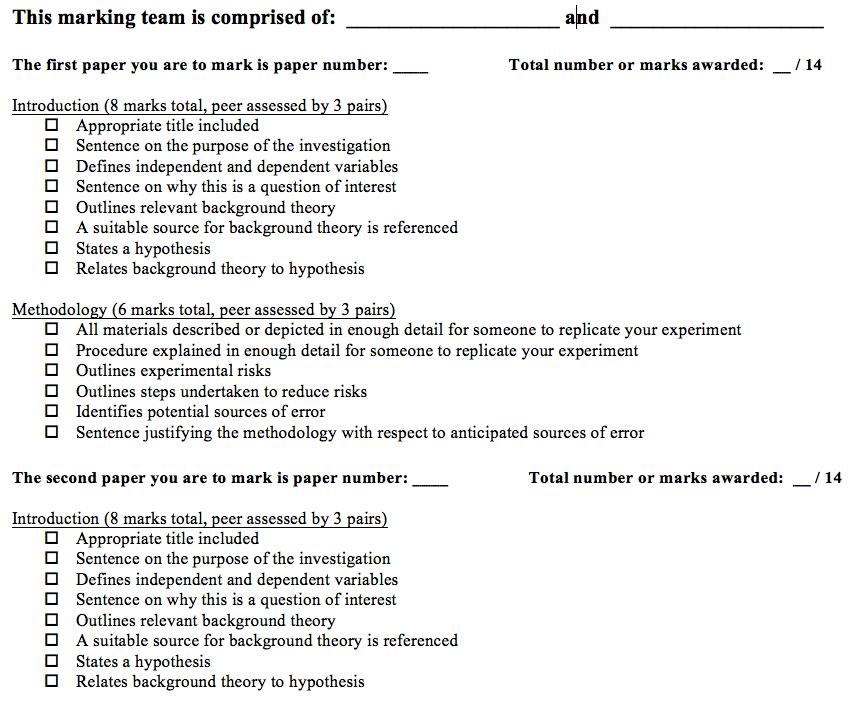

Luckily, anyone can mark surface structure! So it pretty quickly became apparent to me that the the sensible way to do so was peer-marking. Peer marking kills a bunch of birds with one stone, it gives students repeated exposure to the key surface-structure elements that you want them to produce, it gets them talking (if you do it in pairs or small groups) about what does and doesn’t qualify as each surface structure element, it gives them opportunities to see more student work samples, it builds community, and it saves the teacher a bunch of time. Here’s how I did it.

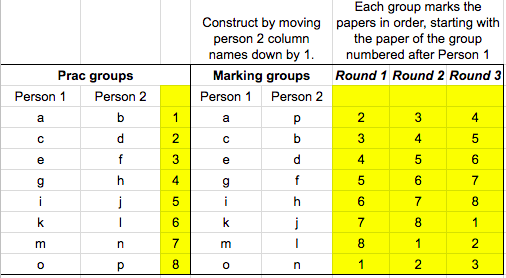

Group students in marking pairs (different from prac pairs/groups) as follows.

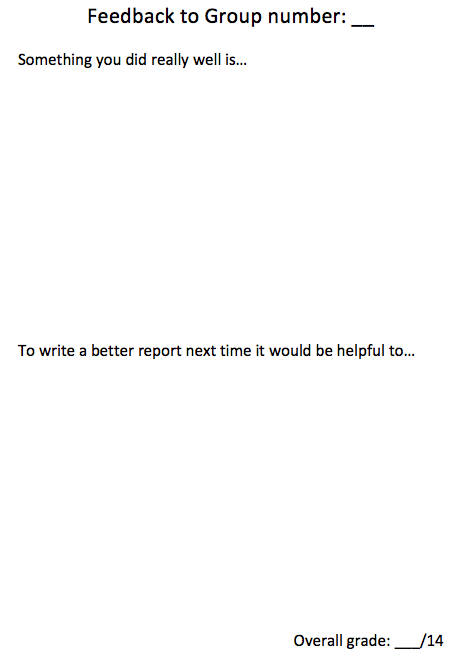

Then each prac report is printed out, de-identified, and placed face down around the room (with the prac group number written clearly on the back). Then students are given a marking sheet, like so (has enough space to mark 3 groups, I just screen shotted half the page)

Thus, each report was marked on surface structure three times by three different groups, and I determined their final surface structure mark by averaging these three results.

I then also gave students an opportunity to provide qualitative feedback to each other, via the following template:

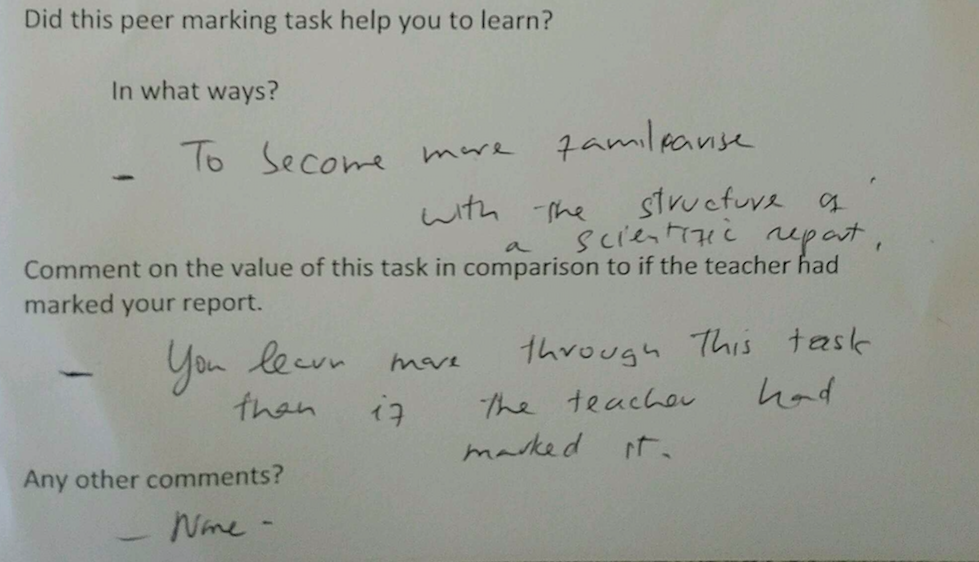

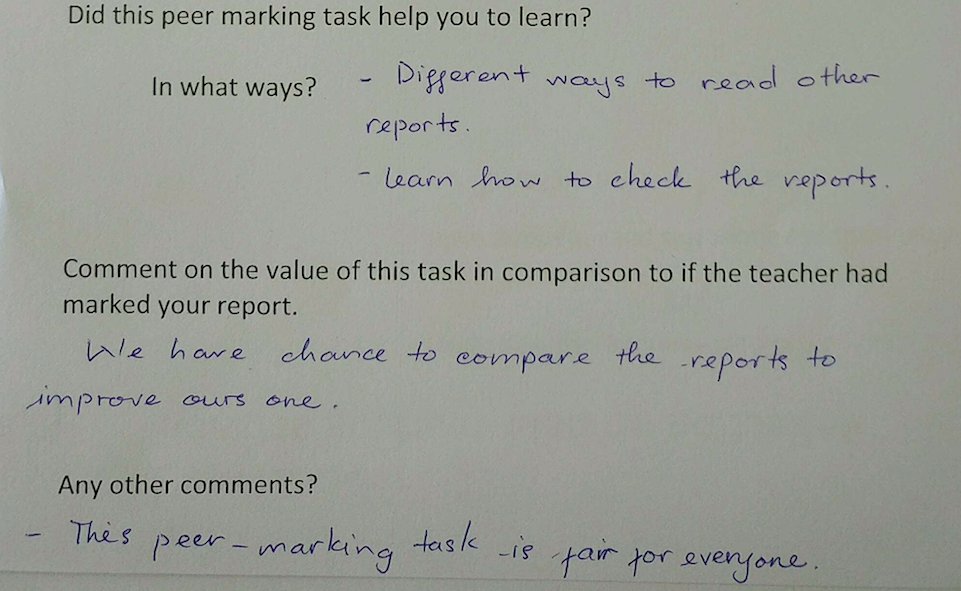

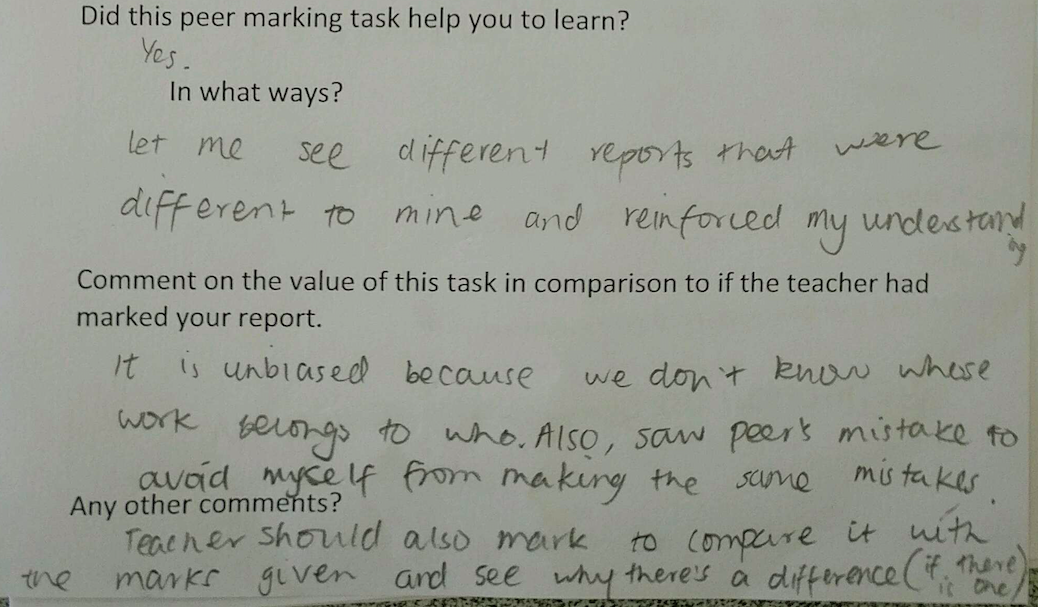

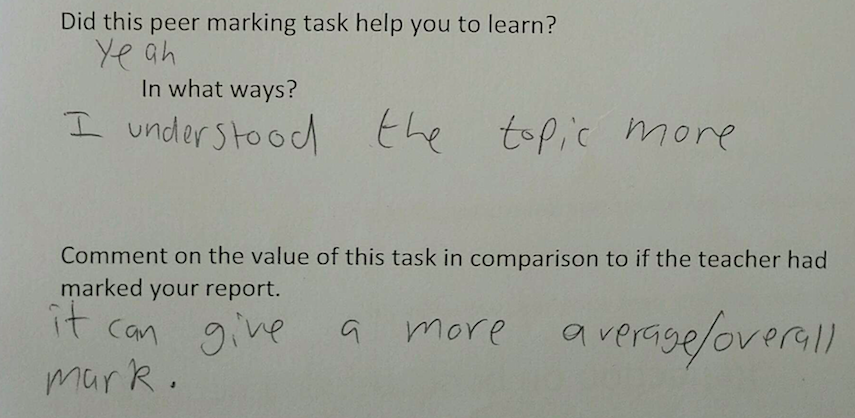

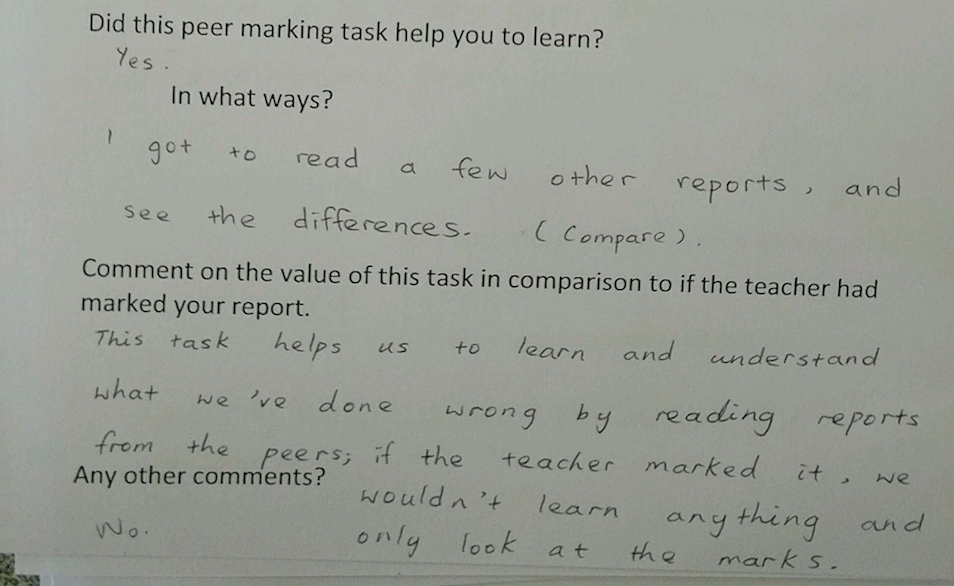

I wanted to see if students like this whole process so I asked them about it. Here are some of their feedback comments:

And here’s the kicker!

The comment immediately above is a paradigmatic example of Dylan Wiliam’s truism “When students receive both scores and comments, the first thing they look at is their score, and the second thing they look at is…someone else’s score” (reference)

Much of this student-feedback (no-one complained, they all liked it) covered things I’d expected: good to see others’ work, good to familiarise oneself with the structure of the report. But I was surprised by the number of students who thought that this was more ‘fair’ or less biased than if a teacher marked it!

The first time we did it as a class I modelled the task for them on the board with a de-identified report then set them off. By the third prac report that we were doing this for, they were totally used to the process and were able to complete the task totally independently.

I was very happy with how this process went and will be continuing it into this year also. The only modification I’m going to make is to allow students to contest a mark if they think it’s incorrect.

Marking deep structure

I’m not happy with how this part of the prac marking went, and this is the portion that I’m looking to modify the most going into this year. It also changed each time I marked each report, and, in all honesty, it was messy. Here’s what I did in the first iteration:

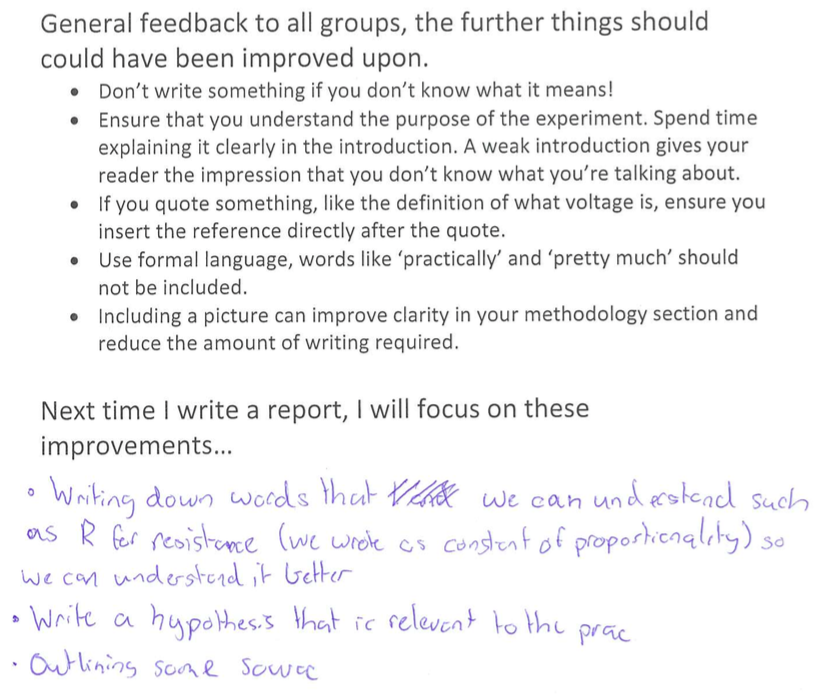

- Cut and paste examples of good and not-so good work into a single document then go through that document as a class, highlighting these things.

- Supplement this whole class feedback with a summary of the things that students should avoid in future.

- Get students to reflect upon how they plan on improving their reports next time.

Here’s an example of one of these reflections, written onto a scaffold that I provided to all students:

As you can see, this basically amounts to something slightly more specific than ‘I’ll do better next time’, but it isn’t super convincing that they will do better next time, nor does it express whether or not they know how to do better next time. Additionally, most of the students had lost this sheet by the time we came to write our next report!

In the final iteration I tried writing a whole heap of personalised feedback to each student regarding the deep structure of their report. HOWEVER! In doing so I broke the (or at least one of the) cardinal rules of feedback: Feedback should be more work for the recipient than the donor (point 4. of Carl Hendrick’s awesome summary of key principles of teaching here). And I frankly felt pretty deflated because I knew that students would just look at their mark and pretty much ignore this feedback all together anyway…

Doing better next time?

So, how to mark deep structure this year?

Well, the main thing is to make sure that my feedback is more work for my students than it is for me. The way I’m planning on doing it this year is to make students submit in two phases. Their first submission will be peer-marked on surface structure, and I’ll give detailed feedback regarding the deep structure and how the report can be improved. I was thinking that this ‘phase 1 marking’ will constitute 50% or so of their final mark. Then I’ll give students an opportunity to take this away, re-work their reports based upon the feedback, then report to me the changes that they’ve made. But, I’ve still got a bunch of things to work out in terms of the specifics. Here are my questions for myself (and anyone who feels like having a crack at answering them):

- How do I want the final version of these reports presented to me? Will I read the whole things again? Will I get them to submit them and only look at the sections that students have re-worked? Should I get students to highlight their re-worked sections in a different colour to make it easier to reference? Or should I get them to present to me orally about this final reworked version (I’m leaning towards the latter).

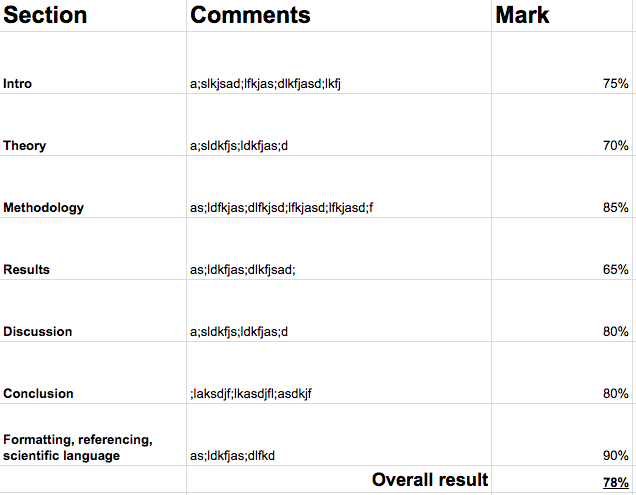

- How will I grade these final versions. Will I have a bunch of criteria with a mark from 1-5 (or a percentage chosen by me, in 5% increments). Or, rather than criteria, should I just assign percentages to each of the sections (e.g., Intro is 75%, Methodology 85%, etc). Or can I just give a global mark based upon ‘the vibe of it?‘.

- Should I use comparative judgment here? I’m tempted, and I feel like it could work well. But I also want to give students an opportunity to explicitly reflect upon the feedback given in relation to the first iteration of their prac report. I feel like the comparative judgment approach could be a bit too general and wouldn’t reinforce the specific feedback that I’ve given earlier. I’m also really wary about marking entire prac reports via comparative judgment. Some reports will have a really good intro but a poor conclusion, or vice versa. Putting two of these side by side I just don’t see how I could say ‘x is better than y’ or ‘y is better than x’ without a more structured approach, especially if they’re on different topics. Should I be grading each section via comparative judgment? But then, that probably going to get real messy and kind of defeat the purpose.

- Could I just use comparative judgment earlier on in the piece? Do I even need this two-stage marking? Is there any way that comparative judgments can support the kind of deep structure feedback that’s necessary for science reports, especially when students are all writing on different topics (I can’t see how this would be possible, but I’m very happy to be proved wrong. I’ll note that I haven’t read Daisy Christodoulou’s book on assessment as yet, but I will as soon as it comes out on Kindle, I really dislike paper books).

- Is Daisy Christodoulou’s book on assessment ever going to come out on Kindle?

- If I do go down the ‘final assessment as oral presentation’ route, how can I do this well? (I’ve literally never come across a blog post or article that talks about this, though I haven’t looked very hard. Where should I be looking?)

- What are my blind spots?

So, at this point more questions than answers, but I feel that the basic deep structure assessment approach (two-stages) is going to be better than what I did last year, will prompt more student thinking, and will generate a better end product. At this point I’m leaning towards a simple template (something like the template below, with comments diligently filled in), that can be used both for the first stage marking/feedback, and for the second stage, which I’d really like to do as a discussion with the student.

So, that’s where the process is at. If you’ve got questions, comments, thoughts, reflections, or advice, please share them in the comments below, or via twitter (@ollie_lovell) or email. I’d appreciate any suggestions as to how to improve the process : )

Hi Ollie, this is a great post. Very generous of you to share your thinking. The detail really helps. I found the idea of splitting surface and deep structure useful and interesting. I’ve tried the surface stuff with younger pupils, but gave up because all they cared about was handwriting. And they thought their feedback was more important than mine. However, if I’d persevered, at least I might have got better handwriting!

Your progress with deep structure is interesting. I’m worried at how much time you spend on written feedback – I see you are worried too! After watching some excellent English lessons this year, I’m convinced that reading 5 scripts during the lesson (or more, but still a sample afterwards), you can identify the most important feedback for all and teach to that. Time is our key resource and I’m convinced that we are all guilty of using this time efficiently (I’m personally convinced that a healthy social life and plenty of sleep make me a better teacher).

Two thoughts from your bullet points near the end: I agree with you about CJ – just judge a key part of the writing, not the whole thing. I’m pretty sure most judges only look at the first page. Second – I haven’t found a way (other than the sampling strategy I mentioned above and the generation of specimen texts) to use CJ to give formative assessment.

It was a great post and really helpful. Thanks,

Ben

Hi Ben. Thanks for taking the time to reply.

Regarding identifying common feedback to all pupils based upon 5 scripts, I definitely agree that this is helpful in many cases, and it’s something I’ll definitely be doing (whole class feedback). However, a few contextual factors make me feel like there’s really no way that I’m going to be able to get away from detailed marking of each students work.

Firstly, this is a major assessment piece in Y12 physics that I’m talking about (the only science class I’ve got), and it’s basically the only writing that they’ll be doing (and I’ll be marking) in the year*. So I don’t think that spending 30 mins on each student’s paper is too onerous of a task, especially as the way that I’ve structured it means that that feedback will be acted upon.

*This is half true, I’m working on helping them structure answers to questions such as ‘Explain the induced current in the loop due to the approaching bar magnet’ too, which I do through drafting and re-drafting in real time as a whole class. But that’s very small writing task, and doesn’t require any marking from me, I just get students to read out or verbalise their response.

Secondly, I need to be really sure of my ranking of students, as this has a large impact on their graduating marks. (I understand CJ can rank, but wouldn’t want to do so based upon just a first page).

Thirdly, each student is doing a different prac (a requirement of the course), thus, there’s no way to spot conceptual flaws in each student’s prac/write up other than reviewing each one individually and in sufficient detail to spot such flaws.

Finally, I’ve built in a 4 week marking window for myself and, whilst it’s a big class (18) I should be able to do justice to the amount of time that the students will have put into these projects, as well as still get a good night’s sleep ; )

Interesting what you say about not using CJ for formative assessment. I tweeted to Daisy C about this a while ago and she said it’s an excellent formative assessment tool, but I haven’t seen any blogs about this from anyone (again, haven’t read her book, it might be covered in there). At this point I’m really interested in CJ but I’d have to be involved in a CJ project in much more detail in order to understand how it works for longer pieces which contain multiple dimensions. If it’s true that essays are marked just on the first page, that’s a bit of a worry, e.g., one of my colleague’s English students last year was an excellent writer, but was excruciatingly slow. In exam’s he’d only manage to write the intro and half of a first paragraph. If he was CJed against other students, he’d probably come out on top if it was just based upon the first page! So yeah, an area of more exploration for me. Please let me know if you write more about.

Thanks again for your thoughts Ben, and I look forward to hearing more about your approaches in future. Ollie.