This is part of a series of blogs detailing a discussion that I had with John Sweller in mid 2017. See all parts of this series on this page.

OL : So, CLT has a complex relationship with motivation. This is out of some more of Michael Pershan’s writings on CLT. Pershan referenced your work with Merrienboer from 2005 and how that paper talked about four major developments in current CLT research. One of these developments was that we should take learners’ motivation and their development of expertise during lengthy courses or training programs into account. Indicating that that was something that CLT was starting to look at. But then, Pershan points out how, in 2012 when you were interviewed, you said: “One of the issues I faced with Cognitive Load Theory is that there are at least some people out there who would like to make Cognitive Load Theory a theory of everything. It isn’t. […] It has nothing to say about important motivational factors…It’s not part of CLT.”

So in terms of right now, where is your thinking in terms of bringing together CLT and motivation?

JS: Motivation is incredibly important. I want to emphasize that before saying what comes next. I don’t think- and in the earlier days I thought it may be possible-I don’t think that theories of motivation should be mixed up with theories of cognition. It doesn’t mean that motivation is not important. It just means that I don’t think you can turn Cognitive Load Theory into a theory of motivation which in no way suggests that you can’t use a theory of motivation and use it in conjunction with cognitive load theory. So it’s really another way of saying: Look, you can make anything either motivating or demotivating. You can give people problem solving, learning through problem solving and a lot of people say, ‘one of the reasons we use problem solving is it’s motivating’. It’s motivating sometimes, for some people, but it’s terribly demotivating for others at other times. A lot of people who become math-phobic become so because they’re demotivated. “Yeah I’ve tried to solve this problem but I couldn’t, I don’t want to see maths ever again!” Same with worked examples. You can organise worked examples in such a way that people are completely demotivated. “I don’t want to look at these worked examples. It’s boring!” You can make it interesting. Anything you teach can be made either interesting or boring. It could be motivating or non-motivating. And it’s got nothing to do with Cognitive Load Theory.

When you look at the alternatives we look at in Cognitive Load Theory, all of them could be either motivating or non-motivating and should they be motivating? Yeah! And motivation is absolutely critically essential to everything, like when you’re standing in your class and you’re using perfect instruction from a cognitive load perspective and its being done in such a way that the kids are staring out the window bored, it doesn’t matter how good the cognitive load instruction is. They tend to be separate and we haven’t really managed to do a great deal with it.

At times it looks as though we might be able to do something in that people have suggested, look, lack of motivation simply means that you’re using your working memory resources on something other than what you ought to be working on. In other words, instead of using your working memory resources on the Mathematics, you’re using your working memory resources on what’s going on outside the window. There may well be a connection there. But it hasn’t gone very far yet. If it goes somewhere then I’ll change my mind as you might gather just by looking at the history of Cognitive Load Theory. I’ve tend to flip flop on this. Right now, I’ve got my doubts simply because of the history of the sort of failure to be able to bring motivation into the cognitive structures that we use in Cognitive Load Theory. It suggests to me, yeah we ought to be looking at motivation, but it’s a separate topic. I understand from your email that you’re going to be talking to Andrew Martin (podcast available here). Andrew, as you know, is a motivation researcher. He’s talked about motivation and Cognitive Load Theory. I don’t think he’s attempted to sort of unify them into a single theory.

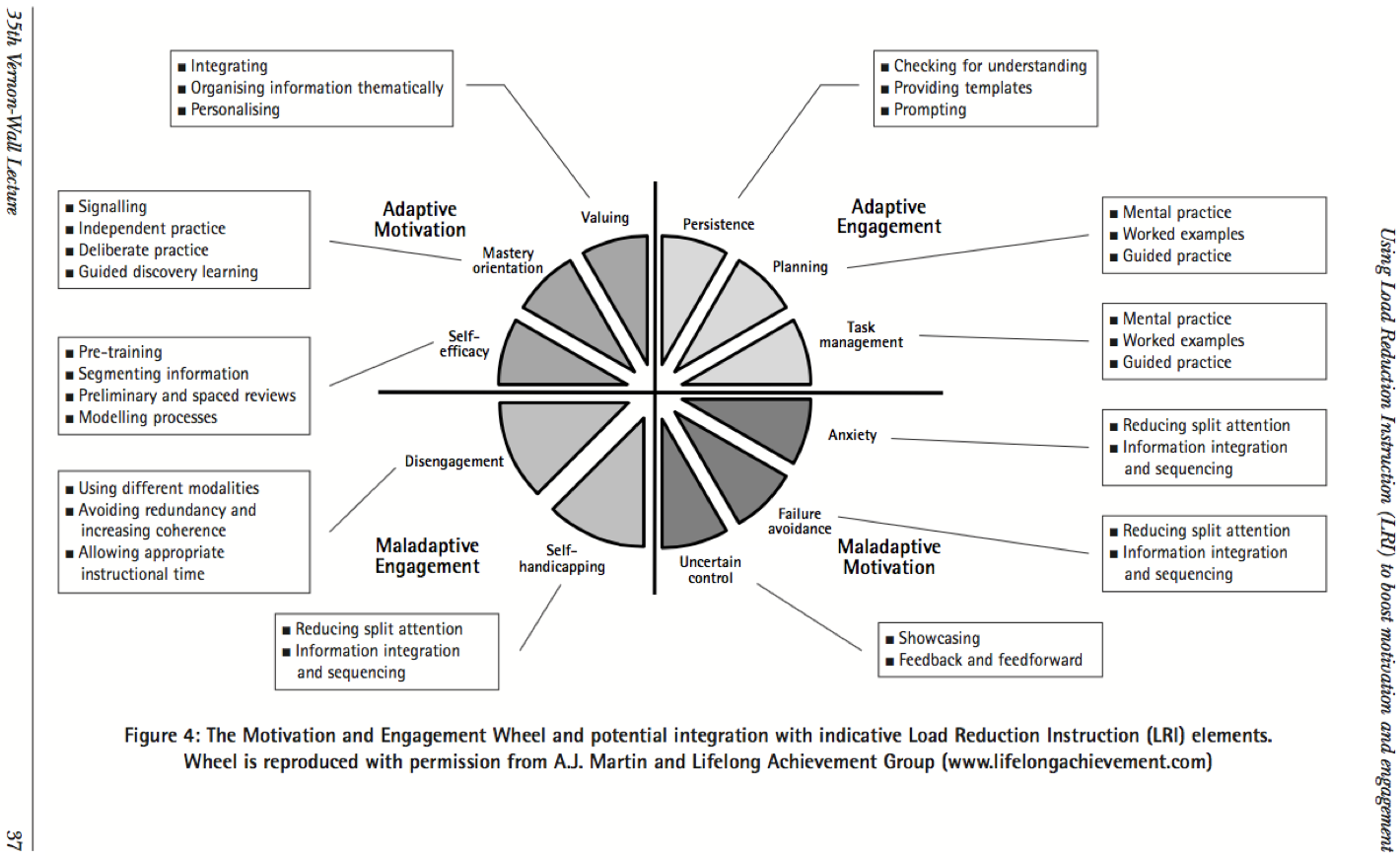

OL: That’s pretty much what he’s been doing. I’ll give you a picture of a diagram that comes from his work because I’m sure it will interest you.

OL: It’s from his paper called ‘Using load reduction instruction increase motivation engagement’. So, he is talking, in some ways, about potential causal relations but he does say several times throughout the paper ‘This is not prescriptive nor is it exhaustive’. This is simply suggested relationships between these various constructs and instructional approaches, all of which require further research. That’s what I took out of it.

JS: Yeah, I should ask him about some of the relations in the diagram that I don’t understand. For example, he’s got disengagement here. But I don’t know what it means to have the line connecting disengagement to using different modalities.

OL: I think he thinks that if you use different modalities if you avoid redundancy and if you allow appropriate instructional time; that can help to boost engagement.

JS: Yeah but I’ll need to find out why particular cognitive load effects are related to particular emotions. I need to ask Andrew why, for example, different modalities would address disengagement while mental practice, worked examples, guided practice wouldn’t. I’m sure there is a good answer.

OL: Let’s just jump up quickly…let’s just find ‘disengagement’ in the paper.

Disengagement is complex and can arise for many reasons (Finn & Zimmer, 2013). It may be that the student lacks particular skills in a domain such as literacy or numeracy, or self- regulation skills such as study and organisational skills (Covington, 1992, 2000). In some cases there are motivational problems such as low self-efficacy (Bandura, 2001), low valuing of the domain or tasks within it (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000), or uncertain control leading to helplessness (Abramson et al., 1978; Weiner, 1985). From a cognitive psychology perspective, it may be a function of the instruction or task itself that over-burdens some learners’ cognitive capacity or renders the instructional material uninteresting and repetitious, leading to abandonment of effort (Sweller, 2012). Approaches under the LRI (Load Reduction Instruction) umbrella can be a means of addressing many of these factors that can underpin disengagement. Here the discussion centres on using different modalities, avoiding redundancy, increasing coherence, and providing appropriate instructional time. (pg. 33)

JS: Yeah, I understand that.

OL: So here it is, ‘…can be a means of addressing many of these factors that can underpin disengagement.’ But I see what you’re saying. That could be said for all/most of the constructs in the motivation and engagement wheel pictured.

JS: Exactly. And I need to find out from Andrew why some constructs go together but others don’t.

OL: Ok that’s good. So at the moment you feel that they’re relatively orthogonal?

JS: I suspect so but I’m sure Andrew has some reason for connecting particular constructs.

Next post:

6. Productive Failure – Kapur (What does Sweller think about it?)

All posts in this series:

- Worked Examples – What’s the role of students recording their thinking?

- Can we teach problem solving?

- What’s the difference between the goal-free effect and minimally guided instruction?

- Biologically primary and biologically secondary knowledge

- Motivation, what’s CLT got to do with it?

- Productive Failure – Kapur (What does Sweller think about it?)

- How do we measure cognitive load?

- Can we teach collaboration?

- CLT – misconceptions and future directions

2 Replies to “John Sweller Interview 5: Motivation, what’s CLT got to do with it?”

Comments are closed.