What does a boat anchor do? … It stops a boat from floating away.

What does a boat anchor do? … It stops a boat from floating away.

What does a memory anchor do? … it stops a memory from floating away.

Whenever you learn something, the new piece of information MUST be connected to something you already know. Here’s an example: Try to remember the following sentence.

“The procedure is actually quite simple. First, you arrange items into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities, that is the next step; otherwise, you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. “1

For the average person, recollection of much of this paragraph in isolation is near impossible. There is simply nothing solid for your brain to take a hold of. So let me throw you a bone (or an anchor): You’re Washing Clothes! Now re-read the sentence, I’m guessing your retention has greatly improved : )

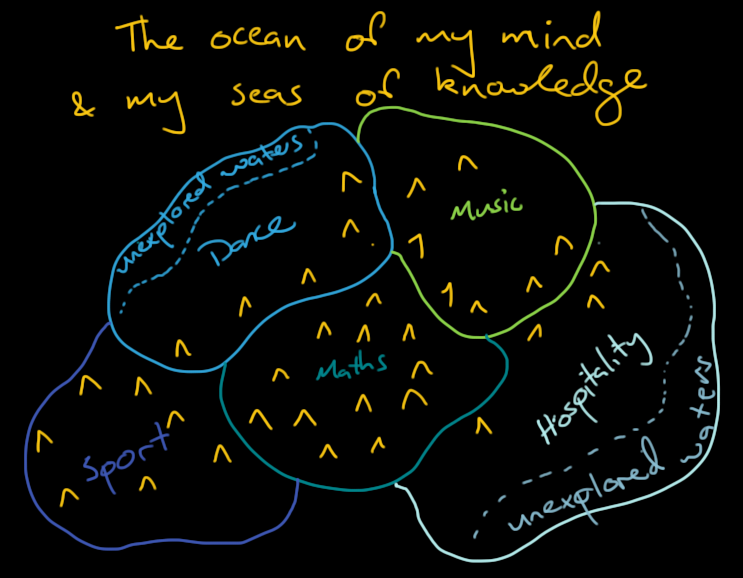

To make this a little less abstract let’s continue on with our ‘voyage of learning‘ analogy. Below I’ve drawn a picture of ‘the ocean of my mind and my seas of knowledge’. We can think of every fact that I know as a ‘fact island’ sitting in one of my seas of knowledge (each sea representing different topics). We can think of learning new things as island hopping. To explore new waters and discover new fact islands I need an existing fact island near by to anchor and rest for the night2.

So Why is Knowledge like Money?

As you can see in the image above, in some of my seas of knowledge I’ve already discovered many fact islands. Maths, music and sport are three areas that I’ve learnt quite a bit of over the years and, as such, I have many fact islands off which to anchor new knowledge. What this means is that if I want to discover more fact islands that are harder to get to in those particular seas of knowledge, I have many more anchoring options to choose from. This makes exploring deeper knowledge in any area (maybe these are under water islands, maybe even underwater caves!) more accessible. To get to the unexplored waters of hospitality or dance it helps if I first find some fact islands on the way to those waters and will reduce my chances of getting lost at sea!

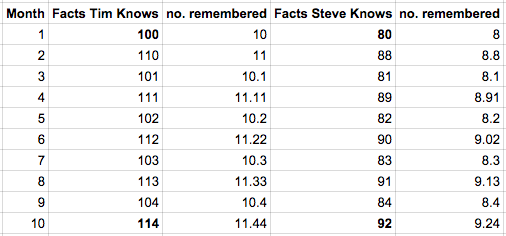

Here’s an example with some numbers about how new knowledge is easier to gain the more you know 3. Imagine Steve and Tim are embarking upon a 10 month maths course. At the start of the course Tim knows 100 maths facts and Steve knows 80 maths facts. Assume that each month they’re exposed to 20 new facts but the number of facts remembered depends on how many they already know (because they have more fact islands off which to anchor the new knowledge). To be precise, they can retain a number of new facts per month that is equal to 10% of the number of facts that they already know. We can see how Tim, who starts out with more, ends up with even more! In month 1 Tim knows 20 more facts than Steve, by the end of month 10 he knows 22 more than Steve. Obviously the numbers in this example are completely made up, but it shows how

So How Do I Anchor New Knowledge?

When you learn something new it is important to ask yourself “How am I going to remember this?”. If you already have a lot of knowledge in the area then when you learn something new you may think ‘There’s no way I’m going to forget this, it’s obvious now that I know it’, which is great (but may be wrong, beware!). However, it’s likely that if you are in knowledge seas where you haven’t discovered that many fact islands yet, it will be of great help to you to explicitly relate this new piece of information to what you already know. You can do this in one of two ways, you can anchor for meaning or you can use a mnemonic. To find out more see the next 2 posts in this series.

- Memory 102:Anchoring for Meaning-How you Think Determines How you Remember

- Memory 201:Mnemonics-supercharging your memory

Notes

- Bransford, J. D., & Johnson, M. K (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding ; Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour, 11, 717-726. (As Cited in Willingham, D. Why Students Don’t Like School, 2010. Kindle location 678)

- There is no doubt a physical basis for this fact that new knowledge must be connected to old in order to be retained. As memories are established activation paths of neurons (ie: a heap of neurons that are connected in such a way that an electrical signal can pass through each of them, thereby activating different parts of the brain, creating a sensation of re-lived experience or knowledge). This is an area that I plan to continue to explore and hope to be able to give a more solid description of how memory anchors work at some point in future.

- Based on Table 1 from Daniel Willingham’s Why Don’t Students Like School?, Kindle location 832.