‘Factual Knowledge Precedes Skill’

This is the ‘guiding principal’ in chapter 2 of Daniel Willingham’s Why Students Don’t Like School. I’ll start by pointing out that this title for Willingham’s book is a bit misleading and the subtitle ‘A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom’ gives readers a much better idea of the book’s content.

Willingham’s book is an excellent overview of 7 crucial cognitive principals that are of great value to anyone who is interested in teaching and learning. In fact, the book in large part inspired this set of posts (of which this is the first) for me and I’ll be going over each principle in detail in the coming weeks.

Of all of the lessons in the book, this one was for me the most profound.Why? For many years I have been of a certain mind that “we are wasting our time teaching kids facts at school, what we need to be teaching them is how to learn and how to think critically!” Whilst I still firmly believe that learning how to learn and critical thinking are… critical, this chapter helped me to realise that:

“Data from the last thirty years lead to a conclusion that is not scientifically challengeable: thinking well requires knowing facts, and that’s true not simply because you need something to think about.The very processes that teachers care about most—critical thinking processes such as reasoning and problem solving—are intimately intertwined with factual knowledge that is stored in long-term memory (not just found in the environment).”-kindle location 552

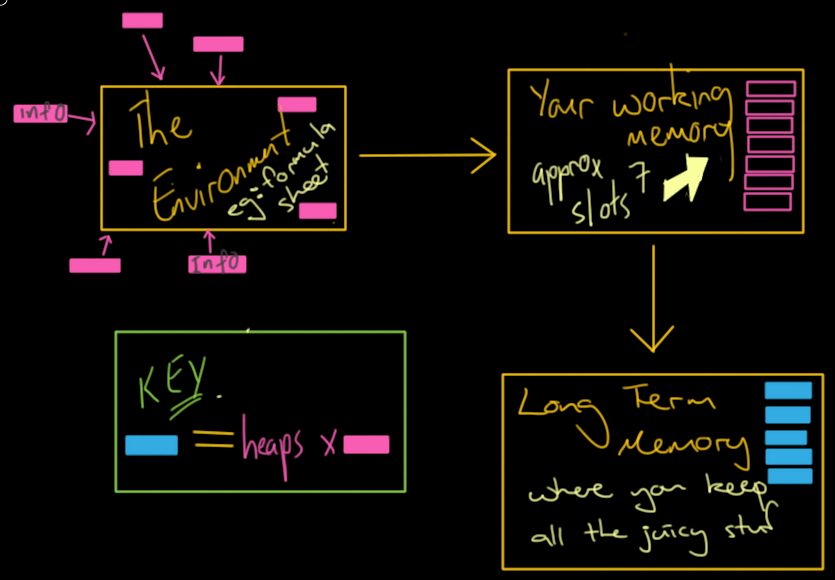

…It’s all to do with working memory. Here’s (my elaborated version of) “Just about the simplest model of the mind possible” that Daniel introduces in Chapter 1. Let’s talk through it

When we begin to solve a problem, 3 windows of our mind are engaged, The environment, our working memory, and our long term memory. The environment is where the question is posed, it’s also where we have access to other information like youtube clips, formula sheets, the working of the kid sitting next to us, and so on. Long term memory is where we store all of the stuff that we’ve already learned. Working memory is where the processing happens. So when we solve a problem we can draw both from our long term memory and from the environment to come up with the solution. If that’s all there is to it then theoretically we should be able to solve any problem as we have access to a seemingly limitless amount of information, but there’s a catch, your working memory only has about 7 slots. 7 precious slots with which you can work*. The reason why long term memory (knowing stuff) is so important is that by remembering stuff you can compress many individual pieces of information and concepts (represented above as pink blocks) in such a way that they only take up one slot in working memory (ie: 1 blue block=many pink blocks). This process is called Chunking and it frees up working memory space for additional info and processing facilitating higher order and more complex thinking. This has important implications for teaching/learning techniques such as the use of formula sheets and scaffolding.

* (7 plus or minus 2 slots covers the majority of the population)

For an example of this please see the bottom of this page.

This information has completely changed my view of what it means to ‘learn’ something…

“I don’t have to memorise anything because I can just put it onto my formula sheet.”

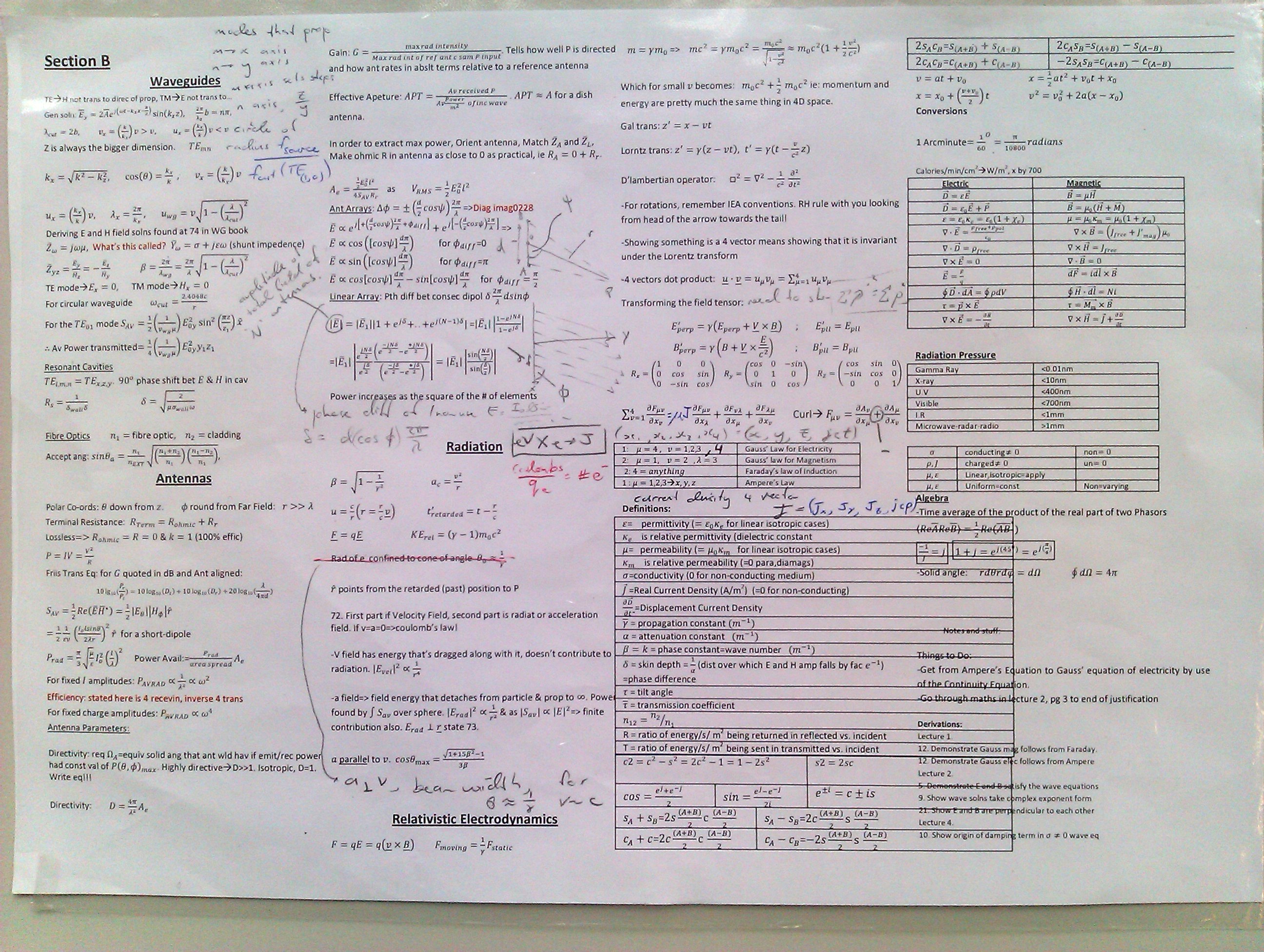

This was my mindset throughout the majority of my undergraduate degree in Physics. See the picture below for an example of one of these such sheets (which we were permitted to take into exams).

After reading this chapter of Willingham’s book I now better understand why I found some parts of my degree as challenging as I did. My ‘I’ll just put it onto my cheat sheet’ mentality was actually preventing me from taking my Physics to the next level. The 7 slot limit of my working memory was being overwhelmed. I hadn’t memorised important facts and info sufficiently for me to ‘chunk’ them, which was limiting my ability to combine concepts in creative ways to solve problems. This conclusion has opened my eyes to the importance of storing things in long term memory and from now on I’ll be making a more concerted effort to use programs such as Anki to do just that! (also the reason why I’m changing my Wot-I-Got blog post format and will be introducing more mnemonics to help readers/my self to better remember blog post content in future).

Conclusion

So, are facts more important than critical thinking? Well… it’s more that facts are a precursor to critical thinking. Knowing facts frees up the processing power of your brain to analyse new information as it comes in.

But this isn’t the only reason why learning facts is super important. Another reason is because knowledge is like money, the more you have the easier it is to get. This is the topic of the next post in this series (coming soon).

If you liked this post you can sign up for all of my posts on learning, teaching and living to be delivered straight to your email inbox (absolute maximum of 1 email per week. Don’t worry, I hate spam too!)

An example of how we’re limited by our 7 slots.

Let’s consider the importance of knowing stuff with an example.

Q: If the nightly revenue of a restaurant is represented by R=-20c2 + 200c + 1920 (where c is no. of customers per night) use calculus to find the maximum nightly revenue.

Without being too exhaustive let’s list some of the things that someone would need to know to answer this question. (think of each number as a pink block)

- How to read

- What a restaurant is (etc, etc, etc with the really obvious stuff)

- what revenue is

- that c2 means that it’s a quadratic

- that a quadratic equation has a gradient

- That the turning point of a quadratic is when the gradient = 0

- How to take a derivative

- How to set a derivative, R’, equal to 0

- Basic algebra to isolate C once you’ve set R’ equal to 0

- That that’s the number of customers that would generate maximum revenue

- that the R equation relates the number of customers to the revenue associated with that many customers

- That you can sub C into the R equation to calculate to find the maximum nightly revenue possible

Now, to me that looks like more that 7 pink blocks. For pretty much all students we can conclude that they have combined pink blocks 1 and 2 (ie, all the obvious stuff) into a blue block, but after that it’s still clear that other stuff must be ‘known’ in order for them to successfully complete the problem, especially if one of their 7 working memory slot is being taken up with a “I can’t do this, I’m confused” mantra.

From the above it’s hopefully clear that for a student to successfully solve this problem they must have stored at minimum 6 of the above bits of info in their long term memory.

One Reply to “Are Facts more Important than Critical Thinking?”

Comments are closed.