This week’s takeaways are a bit of a mix. We have a few pieces on feedback, a couple of forays into history with Florence Nightingale and Seneca, and a valuable post about consent and how to help students (especially young men) gain a better understanding of it.

Next week will be the 100th Teacher Ollie’s Takeaways, and I’ll be featuring the favourite takeaways from some of the most featured educators from the first 99 takeaways over the past few years! That’ll be one not to miss!

Enjoy 🙂

If you’d like to support Teacher Ollie’s Takeaways and the Education Research Reading Room podcast, please check out the ERRR Patreon page to explore this option. Any donation, even $1 per month, is greatly appreciated.

(all past TOTs here), sign up to get these articles emailed to you each week here.

Helping a student who is stuck – three options, via @mpershan

When a student calls us over with a question, it can often be hard to know how to help. I’ve met teachers who have an unwavering conviction that students should never be told anything and always guided by questions. Others take the stance to just tell students how to do what they don’t know how to do. As with most things, the best approach is likely to depend upon a more nuanced diagnosis of the actual problem. In this post, Michael Pershan sets out three possibilities for why a student may be stuck, and how to help in each scenario (this post is in the context of maths, but it transfers to other domains too).

Possibility One: I need to teach the student something, so I sketch a quick example.

When an individual student needs to learn something new in the middle of the task, it’s never ideal.

I used to handle these moments by trying to nudge the kid along with questions about the task at hand. I’ve come to think that this is a mistake, and now I try to avoid it. Instead, I try to quickly write a related problem with a relevant, worked out solution.

Possibility Two: I need to help the student make a connection, so I remind them of a similar problem.

… If I’ve done a nice job with my teaching, the kids have some memorable examples, ideas, problems or techniques to refer back to when trying something on their own. That way, when a kid tells me that they’re stuck but I don’t think they’re missing something crucial, I can lead with…

-

-

-

-

- Remember the diagram we were studying at the start of class? This problem is actually really similar to that one.

- So this is a complex area problem, and there are always basically two options: add some lines to cut the shape up, or use negative space. Which do you want to try here?

- I see you solved this equation by adding two to both sides. Why not do something similar here?

- Remember the diagram we were studying at the start of class? This problem is actually really similar to that one.

-

-

-

Of course, this only works if the students have some prior knowledge. I often lead with this and see if I get a catch. If I don’t, maybe I’ll start thinking about Possibility One.

Possibility Three: I need to help a student realize that they can handle this on their own, so I redirect the student back to the problem.

Sometimes the only thing a student doesn’t know about some math is that they know it. (Which is something that they need to know.) In situations like these, my job is to either reassure the student that they’ve started down a good path, that they aren’t breaking math, or to deflect the question in a way that puts the work back on the kid.

I feel as if there isn’t much more to say about this possibility — it’s the one that math educators generally love to talk about, because it’s the most fun. And, come on, it is fun. How cool is it that the following interaction actually works, ever?

Student: Hey I’m totally stuck.

Teacher: OK what if you weren’t stuck?

This absolutely works, but only sometimes. To get roughly precise, it only works (roughly) a third of the time, because there are two other possibilities.

Other moves that are fun when we’re just trying to redirect attention back to the problem:

-

-

-

-

- What have you tried so far?

- What haven’t you tried?

- Why did you write this?

- Talk for a bit about this.

-

-

-

There’s not much magic here. When a student is in a situation like this it’s often just about getting them back into the problem. They probably got nervous about something and stopped early. I do that all the time when I’m doing math, it’s totally normal. Lending confidence is one of the many little things that a teacher can do.

What makes a good education? Via @teacherhead, @Trivium21C, and @sam_gorse

I thoroughly enjoyed interviewing Martin Robinson (@Trivium21C) on his book Trivium 21C and the idea of the ‘Trivium’ more generally a few months back. I recently emailed him and asked,

Have you written anywhere about your work helping schools with the trivium? I’d be very keen to hear more about the extent to which you’ve been able to guide schools to shape curricula in line with it.

Martin’s reply was to link me to this chat with him, Tom Sherrington, and Sam Gorse about Turton School’s approach to implementing a Trivium-based curriculum.

It’s an awesome chat. You can watch it on youtube from the link above, or listen to it as an mp3 (as I did) here.

Feedback, not Marking, via @joe__kirby

Some key principles on feedback from Joe Kirby.

Feedback is effective when it is timely (not too late after the task), frequent (not too scarce) and acted on (not ignored). Written marking often militates against this: teachers burn out and it becomes less timely, less frequent and less acted on by pupils and teachers.

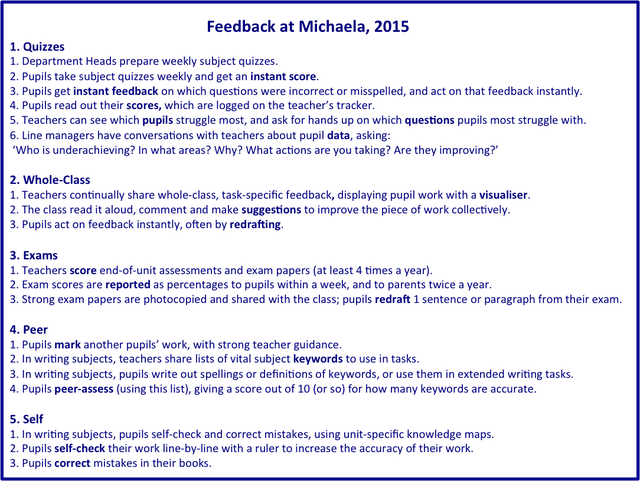

Here’s how this approach is implemented at Michaela Community School (or at least how it was done in 2015). One thing that I’ve been trying myself in terms of feedback recently is the approach offered by Michael Pershan in our recent ERRR discussion together. Primarily, this is selecting a few things that students struggled with in a test (1 or 2 ideally), then, prior to giving the test back, teaching them the skill again with a worked example, having them practice some similar problems, then returning the original test and having them re-work the relevant problem. I’ve felt it worked really well and will continue working on this approach.

The wonderful statistical work of Florence Nightingale, via @TimHarford

A few weeks back I suggested Cautionary Tales as a podcast well worth checking out. This week I listened to their episode on Florence Nightingale and I absolutely loved it. It tells us all about Nightingale as a nurse but, just as importantly, as a statistician. And it’s told in a dramatic style with voice actors contributing. I’m loving this podcast!

Check it out here or in your fave podcasting app.

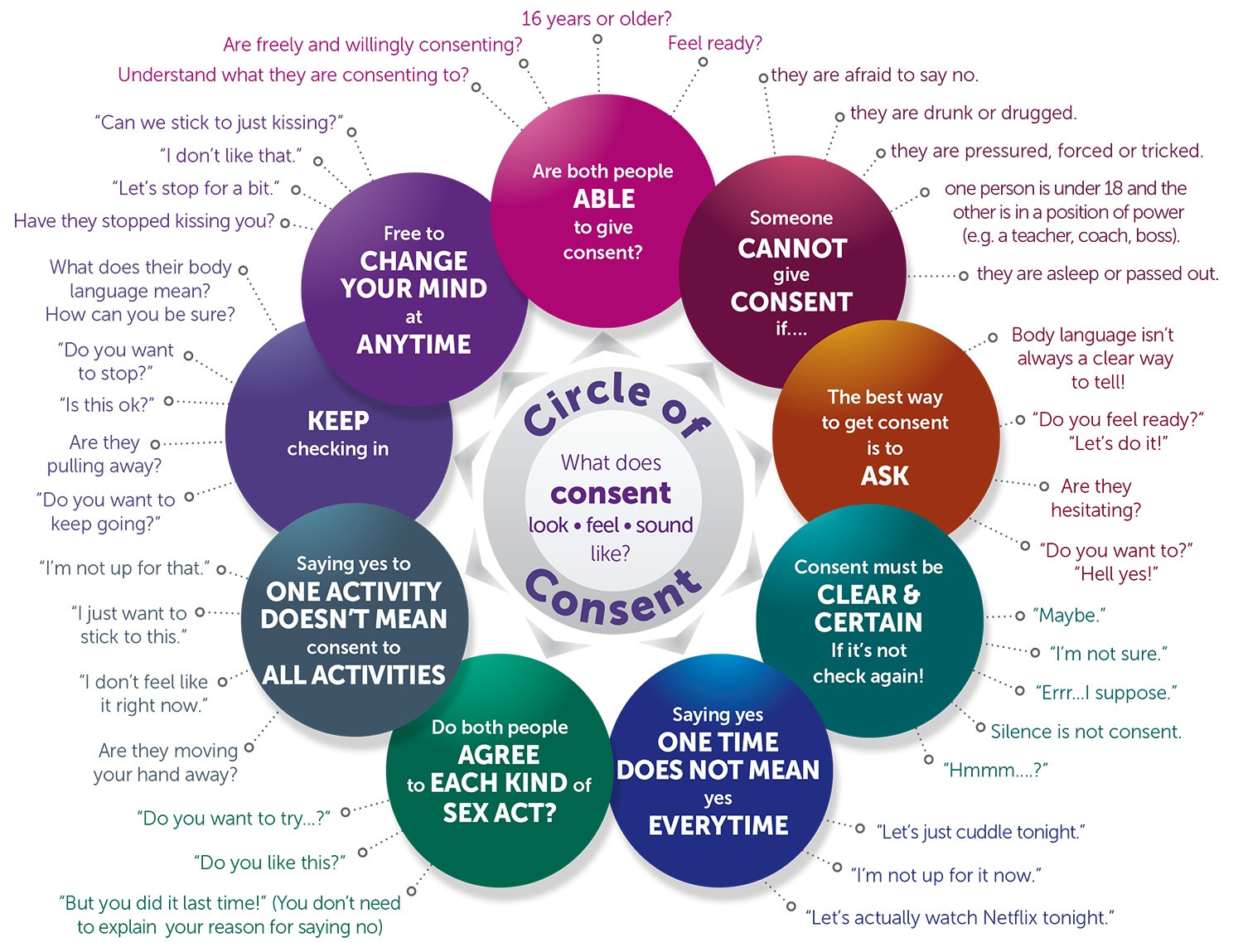

Discussing consent with your child, via Ray Swann at @BrightonGrammar

This week I found this to be a really good article on consent and how to approach discussing it with young people. This is a topic that is gaining a lot of focus in the media at present, and an area that Brighton Grammar (an all boys school in Melbourne Australia) has been doing a lot of proactive work on over the past few years with their +M (positive masculinity) program.

I thought this was a great diagram from the blog:

Source: Talk Soon, Talk Often p18

And here is the practical advice from the article on how to speak to your child about consent.

How you can help

In the early years:

-

-

-

-

- Use the correct labeling for body parts. When we use different or coded words, it can cause confusion and make it seem that there is something secretive about our bodies.

- Reinforce the idea of body ownership: every individual has control over his or her body

- A simple action here is to underline that ‘no means no.’ If your child asks you to stop tickling them, then model that.

- Talk to your son about the importance of ‘telling’ and that different levels of access to him is okay. For instance, a hug from mum or dad is different to that of a stranger.

-

-

-

In the upper primary/lower secondary years:

-

-

-

-

- In these years, it is possible to talk about permission, consent and coercion. You can talk about physical boundaries, but also personal boundaries.

- You can talk about gender roles and responsibilities. This is important as a lack of understanding of diversity of roles and responsibilities can lead to misconceptions about consent (in that men are dominant for instance).

- In films, where objectification occurs, talk openly with your son about the way in which the female characters are portrayed and what that means

-

-

-

Middle to later secondary years:

-

-

-

-

- Talk about power dynamics in relationships and what a healthy relationship looks like

- Check in with your son about the content he has covered at school

- Discuss the role of alcohol (and drugs) and the potential effect this can have on the understanding of boundaries and giving, as well as providing, consent.

-

-

-

As the Harvard report states, ‘these conversations often don’t need to be painfully awkward, deliberate, face-face conversations. There are countless opportunities to address these issues more informally’ (Wesissbond et al, 2017).

Dealing courageously with sickness, via Seneca

Last Friday I heard of a father of a friend who has just been diagnosed with a very challenging disease. It prompted me to think about the precarity of life, and how I may react if I encountered some similar news about my own health.

On Sunday, I was reading Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic and came across letter LXXVIII (78) which happened to be on the same topic: how to courageously face a sickness or illness of some kind. I found it to be an inspiring read. (FYI, catarrh is ‘excessive discharge or build-up of mucus in the nose or throat, associated with inflammation of the mucous membrane.’ which I had to google after reading it in the first sentence!)