This is the first in the five steps of efficient learning that are outlined here.

Survey is about working out what you need to learn. This can be thought of in the ‘ask around’ sense of the word, or in the ‘survey the scene’ sense. If you’re preparing for a test, surveying is about finding out what is most likely to come up in the test, if you’re trying to learn a language, Survey is about finding the high frequency words, and learning them first. In this step we are sketching the outline of our learning and trying to recognise patterns in the information that we can take advantage of.

Survey is about working out what you need to learn. This can be thought of in the ‘ask around’ sense of the word, or in the ‘survey the scene’ sense. If you’re preparing for a test, surveying is about finding out what is most likely to come up in the test, if you’re trying to learn a language, Survey is about finding the high frequency words, and learning them first. In this step we are sketching the outline of our learning and trying to recognise patterns in the information that we can take advantage of.

The best way for me to explain this is through examples.

Example 1: Maths exam

2011, Semester 2, 5 days out from my Differential Equations and Linear Algebra exam. I’d really left things to the last minute. I’d just returned from a conference that I attended in the middle of study week and I now had less than a week to learn a 13 week unit that I really hadn’t been paying attention to*. The first step? Survey! The goal of the survey was to identify exactly what I needed to learn to get the maximum outcome with the minimum effort.

This was me doing my best to employ the 80/20 rule. Asking: ‘Which 20% of work will give me 80% of the results?’ Did I try to work through all of the lectures from the unit? No, not enough time. I began with the end in mind. I started by looking at past exams.**

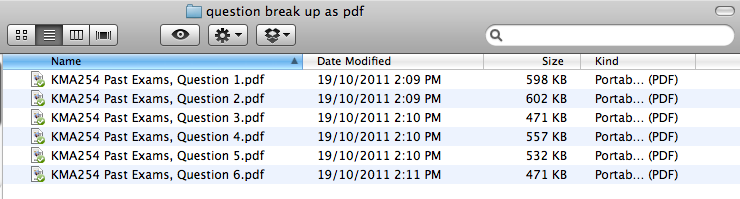

My Survey of past exams spanned the 2002 exams to the 2010 exams (I chose these ones because these were the ones for which the lecturer had been the same, and he was my lecturer that year, so I assumed they would be a good indication of relevant info). I tried to identify similar questions in each exam and I grouped them into PDFs so I could see each ‘category’ of question in one place. Here’s what they looked like in my folder

And here’s an example of what one of the PDFs looked like.

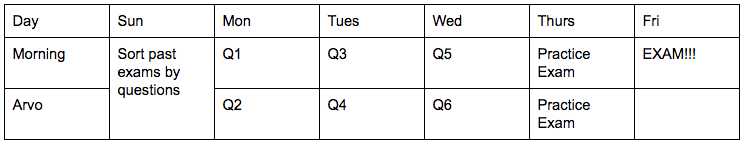

Now, whether you have or haven’t studied Differential Equations and Linear Algebra before, it’s clear that doing this did one thing of great value. It allowed me to identify patterns in the past exams, patterns that I could use to target my study. I now could see exactly what I had to learn to prepare. I spent the next three days looking at one question every morning, and one question every afternoon, here’s a re-make of what my study timetable looked like

I teamed up with buddies to work through questions that each of us struggled with, and I and I got the 80/20 rule spot on, I got 80% for the unit.

*Since this time I’ve learnt a lot about learning and knowledge acquisition and have come to realise the massive weakness of this ‘leave it to the last moment’ approach. If you don’t space your revision you’re really doing yourself a disservice and you’re likely to have the info just fall out of your brain post-exam. Furthermore, I recently found out about the importance of actually memorising things long term for life learning and better comprehension/critical thinking. This completely changed my view of how I studied in my undergraduate degree. I include this example here to express the value of the survey stop, not to glorify cramming!

**Whether this exact technique will work depends on the nature of the unit and the lecturer. In the above, for dramatic purposes, I leave out the fact that I’d chatted to a number of previous students of this class and they’d all told me that the exam was pretty predictable each year. This pre-survey survey gave me confidence that I’d be able to use the survey technique to reduce my study time and learn the content in 5 days.

Example 2: Learning Mandarin

My primary learning project at present is learning Mandarin. I started in November 2013 (10 months ago now) .But how did I start? With a Survey of course. But this survey was different to the maths exam. I wasn’t learning for a test, I was learning for living. So I saw it in a different light. For this survey I employed the most important survey principle that I know: ‘Ask someone who knows‘.

This is a principle that I apply to absolutely everything I start, from calling my grandma to ask her how to cook a christmas pudding to reading books about how the stock market works. In the case of Mandarin, I knew of 1 person who I knew had learned languages quickly before, Tim Ferriss. So I read up on what he had to say about language learning.

This introduced me to Spaced Repetition Software and the idea of Frequency Lists. I then spoke to someone else at a conference and they told me about ChinesePod. Finally, I tracked down a friend of a friend who had taught himself Mandarin and was fluent. We met up at the local library and I we had a great chat. He taught me two vital lessons in that conversation: Firstly, that communication is mostly nonverbal, so when communicating in the language that you’re learning, don’t stress too much about the words, think about the meaning (sounded strange at first but became more clear as I began to communicate more, and allowed me to accelerate my communication). Secondly, it’s ok if sometimes you don’t feel motivated. Just because you stop for a week doesn’t mean that you have to stop for ever. Just pick it up again and keep going.

Conclusion

By taking a step back at the start of a learning experience and asking ‘what exactly do I have to/want to learn and what’s the best way to do this?’ you can help yourself to first see the patterns of your learning task before you move into the detail. Ask someone who knows and sketch out the outline and the main points of the task before you begin. This is the difference between completing a puzzle when you know what the end picture is supposed to look like vs. when you don’t. Scope out the scenery. Do a survey.

I’ll note that both Tim Ferris and Josh Kaufman call this step ‘deconstruction’.