Good week dear readers.

First bit of exciting news is that my podcast with Dylan Wiliam on his book Leadership for Teacher Learning is now out. You can listen here.

Here’s the rundown.

T1 is a great idea that takes 20 seconds to read, check it!

T2 debunks the 10,000 hour rule, or at least adds a lot of nuance.

T3 I found very interesting, I’ve provided a summary of a summary of an interesting study.

T4 follows on from the ‘scaffolding student thinking through writing’ that I linked to in TOT065 (which you might like to check out if you haven’t as yet)

T5 interesting for english teachers in particular.

T6, T7 interesting for those keen on reputable sources of edu evidence and the state of state education in Aus.

T8 is worth a read if you’re not very familiar with ResearchED, the conference(s)

I’ll let T9, 10, 11 speak for themselves and then, excitingly…

This week you’ll also note that I’ve added to the end of the list a new section ‘Thought Shrapnel‘. This is a place for me to just dump a bunch of ideas and thoughts I’ve had, usually prompted by my reading, that I think that readers may find interesting. This new section was prompted by the fact that I’m increasingly enjoying reading books, and that means that my reading of blogs is decreasing a bit. In the interest of continuing to share my key takeaways from the week, I needed to think of a format that would allow me to share the thoughts prompted by these books. This is it, for now. It might change, who knows. Let’s give it a go. Let me know if it is/was interesting to you : )

I should note that I’ve stolen the phrase ‘Thought Shrapnel’ from Doug Belshaw, who does a great post each week sharing some of his thought shrapnel. You can check it out here.

Enjoy : )

(all past TOTs here), sign up to get these articles emailed to you each week here.

The preflight checklist, a great peer accountability strategy from @dylanwiliam’s ‘Embedded Formative Assessment’

Dipping into @dylanwiliam‘s ‘Embedded Formative Assessment’. Really love this technique, the ‘preflight checklist’ . Will definitely be using in my physics class. Also, considering extending to other tasks within the classroom… pic.twitter.com/VEPULLoz9o

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 30, 2018

Problems with deliberate practice: can we use it in teacher education? via @HFletcherWood

‘Problems with deliberate practice: can we use it in teacher education’ a great piece by @HFletcherWoodhttps://t.co/dRAeh0weIP

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 29, 2018

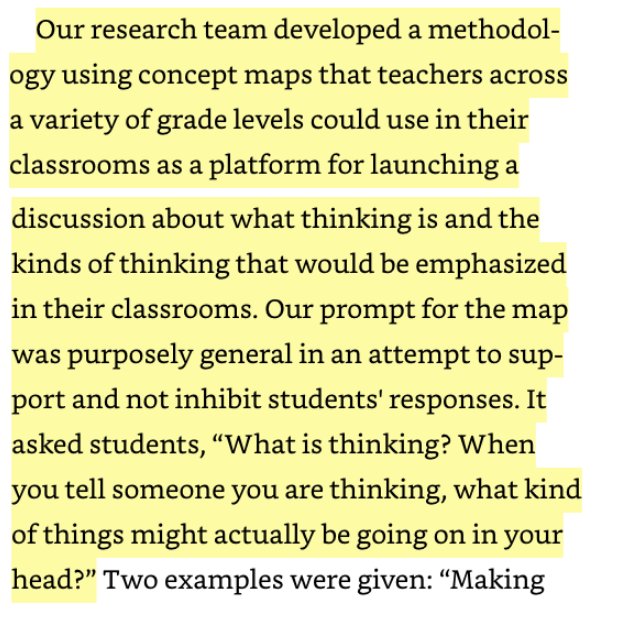

A clever study using concept maps to make students’ thinking about thinking visible, via @ronritchhart

Original thread here.

Here’s another stimulating snipped from Creating Cultures of Thinking

Revisiting intended student and teacher roles/dispositions within your classroom. Explicitly discussing cultural norms. It’s always been clear to me to repeat and re-expose student to the content they’re to learn, never thought to apply to culture! @RonRitchhart #ccotonline pg.91 pic.twitter.com/pjqcev3NGO

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 26, 2018

More on using strategies from ‘The Writing Revolution’ to scaffold writing and thinking, via @rhwave2004

This post details how @rhwave2004 applies some of ‘The Writing Revolution’ principles in her classes. It also introduces the instructional routine of ‘Verb Talks’. Watch this space for more great stuff from Rachel. https://t.co/SyBooobJt9 pic.twitter.com/hjeuHeP7Ex

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 29, 2018

Sensitivity analysis, helping students see what gives a section of text its nuance (with practical examples), via @Doug_Lemov

Sensitivity analysis. Helping students to understand what gives a section of text its feeling and nuance. Some practical examples. Via @Doug_Lemov. https://t.co/GOdKy3Y11L

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 26, 2018

Beware, sometimes the most seemingly trustworthy sources of edu-research are flawed. Re: What Works Clearinghouse

This is a worrying article. Casts much doubt on whether or not @EvidenceforESSA‘s resources are a reliable guide to quality programs. This example comes from the area of literacy instruction. https://t.co/nSAKVabWHn

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 26, 2018

A clear comparison of Australia’s states and territories and how their edu systems are performing, via @peter_goss

“No state has all the answers in school education”. A fantastic snapshot of how our states and territories compare educationally, including suggestions for areas of focus. https://t.co/6RfZV7vd2H via @peter_goss

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 31, 2018

The value of ResearchEd (We’ll probably have one in Melbourne next year!), via @teacherhead

. @teacherhead tells us of the value of ResearchEd. Can we look forward to another one in Melbourne next year @tombennett71?https://t.co/XPj8kcIKtN

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 27, 2018

Resources for incorporating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures into science teaching

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures. Resources for incorporating into science. https://t.co/sqdgtNRnwZ

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 29, 2018

Some thoughts for the budding authors amongst you, via @SamRochadotcom

Been writing, or thinking about writing? This thread is worth a gander. Ht @nomad_penguin https://t.co/cI8z7eNQ2w

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 26, 2018

Maths teachers: Binomial theorem question, how many subway sandwich combos? via @RayBadran

Maths teachers. Here’s a good binomial theorem question for your students. How many different subway sandwiches are possible? https://t.co/Wpkl9yknH2

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) October 31, 2018

THOUGHT SHRAPNEL: Parallels between progs and trads, Why read about culture? Thoughts on marking, Trying out a thinking routine: The explanation game

Progs and trads: Parallels

Made some connections between the ideas of some of those considered on the falsely dichotomous right (trads), and some of those on the left (progressives) of teaching this week.

An excerpt from Ron Ritchhart’s ‘Making Thinking Visible’

In his book Smart Schools, our colleague David Perkins (1992) makes a case for the importance of developing opportunities for thinking: “Learning is a consequence of thinking. Retention, understanding, and the active use of knowledge can be brought about only by learning experiences in which learners think about and think with what they are learning…. Far from thinking coming after knowledge, knowledge comes on the coattails of thinking. As we think about and with the content that we are learning, we truly learn it” (p. 8). (p. 26)…

Well well well, if this isn’t basically the same as Dan Willingham’s ‘Memory is the residue of thought’, and, similarly, ‘What we attend to is what we learn’ from Pep’s Mccrea

In their Minds of Our Own video, an honors chemistry teacher admits that “I don’t like asking ‘why’ questions on tests. I spend so much time covering the concepts then I ask the question, ‘Why?’ and I get back so many different answers. It’s sometimes very depressing to see some of the answers that you get back when you ask ‘Why?’ questions. They are valuable, but as a teacher it is sometimes very frustrating to see some of the reasons students think a certain scientific phenomenon takes place.”

This teacher, far from being cavalier or uncaring, is expressing the bind that he finds himself in when teaching for the test. He knows his students don’t really understand what is being taught, but in the delivery paradigm of education he focuses on covering the material for the test and keeps their thinking invisible so as to allow for the semblance of learning, an illusion that equates scores on a test with evidence of learning.

Ritchhart, Ron. Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners (p. 27). Wiley. Kindle Edition.

This passage, to me, speaks of the importance of formative assessment. The only difference is, I’ve always thought about formative assessment as giving students progress checks, mini whiteboards, etc. But here we’re just doing FA via discussions and making students’ thinking visible through alternate forms. Gives me much hope for this book, and great to see those on what could be considered opposite ends of the instructional spectrum saying exactly the same thing!

(See the end of my recent podcast with Dylan Wiliam in which he encourages us all to listen to those with whom we think that we disagree/don’t like. ‘I don’t like that man very much, I must get to know him better!’)

Why am I reading these books about classroom culture, and making thinking visible?

Essentially, I feel that I’ve put fantastic instructional structures in place, but what I can’t do through structures alone is is to force students to think. This becomes most apparent when it’s revision time, and their motivation is low, and students don’t know how, and aren’t inclined to, do the thinking required in order for learning to take place. The main theme of this year’s learning for me has been thinking of non-structural solutions to problems, when my proclivity is to look for structural ones… it’s my default, because solving problems in my own life is pretty much always just about putting structures in place, whereas that isn’t the case for others. As such, I need to consider wider approaches to scaffolding student learning, it seems to me as though spending more time consciously creating a classroom culture that’s conducive to cognition (alliteration ftw) is probably a good avenue for me to explore.

Some thoughts on marking

There’s much going around at present about marking. Whole class feedback is especially getting a good run (see Mr Kirkman’s fantastic example here!). I was discussing with a colleague the other day how he’s a big fan of whole class feedback, but his wife is super committed to marking her students’ work, student by student, even though it chews up heaps of her time and he doesn’t believe is any more effective. His wife says something to the effect of ‘I just really like to know what my students are struggling with’. My colleague and I both felt that this is true, but there are perhaps less time consuming ways of doing it.

I then read the section in ‘Creating Cultures of Thinking’ entitled ‘Manage energy, not time’. And I considered this scenario against this backdrop.

And I realised that,whilst I find marking a drain, maybe that isn’t the case for my colleague’s wife. Maybe she really enjoys it? Perhaps my colleague’s wife finds this marking a rejuvenating activity? I’ll have to ask her. Regardless, it’s an interesting thought. Always helpful to take different perspectives.

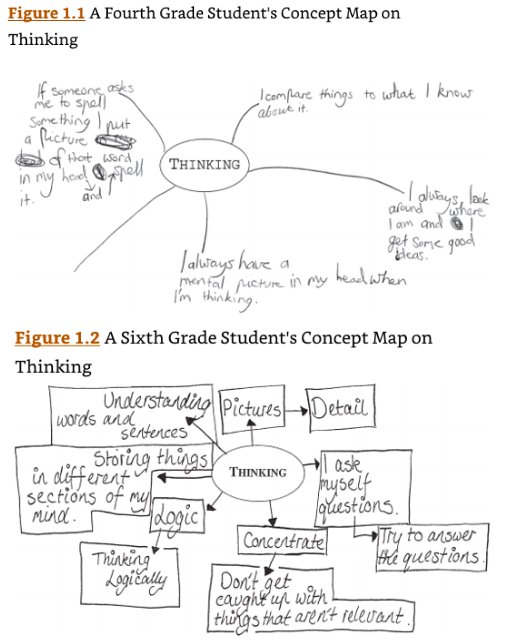

Changing my classroom practice: Thinking routines

This week I’m going to try out one of the thinking routines from Ron’s ‘Making Thinking Visible’… the explanation game… I’ll try to write about it for next week : )

I’ve copied some of the info about the routine below the image. Hope you’ve enjoyed thought shrapnel : )

Steps

- Set up. Draw students’ attention to an object you would like them to understand better. Resist asking the students to tell you what the object is if it is one they don’t immediately recognize; rather, invite them to carefully look at the object to see all that they can possibly see, so that they can begin speculating as to how different features are related to one another.

- Name it. Now ask students to share with their partners various features or aspects of the object they notice. It is important in this stage that students record all the different parts they are observing. This could be done on sticky notes. Working with a partner or in small groups affords students the opportunity to take notice of features they might miss individually.

- Explain it. Once students have accumulated a list of various features they have noticed, ask them to begin explaining these features. It is important that you emphasize the name of this routine here: the Explanation Game. You want to focus the group’s attention on the action of generating explanations, sharing with students that in this step their goal is to come up with as many different explanations as possible. Have students document their explanations.

- Give reasons. Ask students to generate reasons why their explanations are plausible. This step is about pressing for evidence, asking students to articulate what they have seen in particular that makes them say why a certain feature could be explained a certain way. 5. Generate alternatives. In this step, ask students to press for alternative explanations than the ones they initially generated. The goal here is to keep student attention on the relationships between the features of the object they have noticed and why these features might be the way they are rather than coming too quickly to a fixed explanation. For each alternative explanation offered, students should ask one another, “What makes you say that?”

Ritchhart, Ron. Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners (pp. 102-103). Wiley. Kindle Edition.