There are many models for instruction. Often they’re focussed on what it is that the teacher needs to do to facilitate learning.

Existing models:

For example, Danielson’s framework looks at a teacher’s planning and preparation, how they set up the classroom environment, the quality of their instruction, and their professional responsibilities. The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS, Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, 2008) looks at emotional support, classroom organisation, and instructional support. And Rosenshine tells us to do important things like begin each lesson with a review of previous learning, present new material in small steps, with student practice after each step, and to provide models (amongst other things).

A shifted focus

Less frequently, we think about instructional models from the learner’s perspective. However, a focus on what occurs for the learner, rather than what’s done by the teacher, is becoming more prevalent, as is captured in the following ideas that I’ve found to particularly resonate in recent years:

- Review each lesson plan in terms of what the student is likely to think about. This sentence may represent the most general and useful advice that cognitive psychology can offer teachers – Daniel Willingham

- Memory is the residue of thought – Daniel Willingham

- Students remember what they attend to – Peps Mccrea

- Teaching is knowing the difference between, ‘I taught it’ and ‘they learnt it’ – Doug Lemov, referencing John Wooden

- The most important thing for teachers to do is check for understanding – Tom Sherrington

- Instructional coaching goals must be student focussed – Jim Knight

Each of these firmly places the learner at the centre of instruction, and instructional goals.

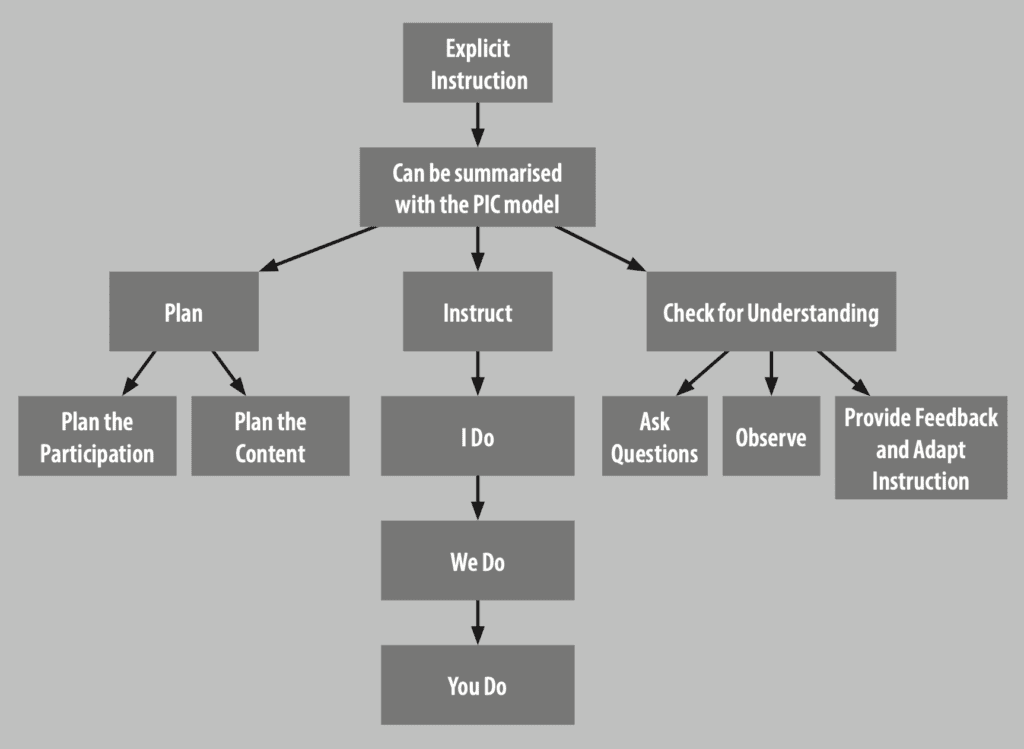

In Tools for Teachers, I proposed a simplified model for explicit instruction, the PIC model, Plan, Instruct, Check for understanding. Which is summarised in this image:

The CAMA model

Building on this, I’ve been thinking more deeply about what lies at its heart, what’s is it that the teacher is trying to support the student to do by taking actions as specified in the PIC model.

In response, I’ve come up with another tentative framework, this time centred on what happens for the learner whilst the teacher is planning, instructing, and checking for understanding. In essence, I feel that there are four steps: Curate, Attend, Monitor, Adjust.

The key difference between these four steps and other models is that they describe the experience of the learner, not what the teacher does.

First, the learner is made aware that there’s some material that they have the opportunity to attend to (Curate)

Next, the learner can choose to allocate their attention to it (Attend)

Thirdly, the comprehension of the learner should be Monitored, either by the learner themselves (monitoring/metacognition/reflection) or by the teacher (check for understanding)

Finally, instruction should be Adjusted in light of the interplay between the initial content that was presented, and the how well the student attended to and comprehended it.

That’s it. That’s all that learning requires (I think…)

Why a mechanism-based model?

This tentative CAMA model has been prompted by a deeper consideration of the consideration of the mechanisms that lie behind learning. Learning is a path from a current knowledge state (declarative or procedural) to a higher one. To make that journey, students must encounter new information, pay attention to it, understand it, and make course adjustments if the current path seems to be failing (Dylan Wiliam uses a similar course + adjustments metaphor in relation to Formative Assessment here). Anything that the teacher does, in an instructional sense, is simply an attempt to help the student to attend to curated information, monitor their understanding, and adjust as needed.

Why consider a simplified, mechanism-based model like this? Here’s an excerpt on mechanisms from Tools for Teachers:

An understanding of mechanisms is key because it allows us to deploy the different components of an initiative at an appropriate time, to save on resources and time by cutting out anything that isn’t absolutely core, and to adapt instruction without leading to ‘lethal mutations’ (alterations that result in the ineffectiveness of your approach).

In short, my hope with the CAMA model, or something like it, is that it’ll help us to deploy, save, and adapt instruction to improve its efficiency.

Let me know what you think! What have I missed? What have I overlooked? How could this be improved?

One Reply to “Four steps to learning: Curate, Attend, Monitor, Adjust”

Comments are closed.