Have you ever heard of the white bear intelligence test? Whoever thinks of a white bear the least is the smartest. So, let’s try it out:

The test starts now: Don’t think of a white bear…

I told you not to think of a white bear! Ok, so you thought of a white bear. But now you really have to stop thinking about a white bear, the more you think about it the dumber you are. Just suppress the thought of a white bear so there is absolutely no image of a white bear in your head.

I said DON’T THINK ABOUT A WHITE BEAR, this really isn’t looking good for your intelligence score…

Obviously this isn’t a very good test of intelligence, so why are we thinking about white bears and trying to suppress these thoughts? Because this is an exercise used by Senay, Cetinkaya and Usaka (2012) to explore acceptance of test-anxiety-related thoughts as a means of helping students to improve their test performance.

For many people, anxiety about tests is one of the main factors that reduces test performance. This occurs because anxious thoughts such as “I’m no good at maths” or “I’m going to fail” or “this is too hard” occupy space in working memory. This reduces the cognitive processing power that’s available to be allocated to actually doing the test (Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001). The default coping strategy for many students is to try to suppress these anxious thoughts, but what can often happen is that (as with the white bear whom we met above) the thoughts just keep on popping up, and sometimes trying to suppress them can just increase their prevalence!

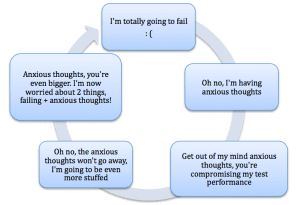

There’s a compounding factor at play here too, and that’s the fact that students often realise that these anxious thoughts are compromising their performance. This adds extra pressure on them to suppress these thoughts (pressure that I tried to simulate above by suggesting that the white bear exercise was in fact an intelligence test [but I probably didn’t fool you]) and can lead to the vicious cycle pictured to the right.

There’s a compounding factor at play here too, and that’s the fact that students often realise that these anxious thoughts are compromising their performance. This adds extra pressure on them to suppress these thoughts (pressure that I tried to simulate above by suggesting that the white bear exercise was in fact an intelligence test [but I probably didn’t fool you]) and can lead to the vicious cycle pictured to the right.

note: It can infact be more like a vicious spiral, with the student getting more and more stressed as the test goes on… but I didn’t know how to make a spiral in Microsoft SmartArt Graphics.

Senay, Cetinkaya and Usaka (2012) wanted to test ‘acceptance’ as a technique to help students deal with test-related-anxiety. They took 87 college freshmen, both male and female who were doing an intro-to-psychology class, and performed the intervention immediately prior to a class test. They split the participants into 4 groups. A control group (told to just do the exam is they normally would), a group who had a 10 minute training on anxiety avoidance techniques*, a group had a 10 minute training on anxiety acceptance techniques**, and a group who received training in both.

*ie: avoid the things that are likely to produce anxiety for as long as you can. In this case the main technique spoken about was to pass any difficult questions and come back to them once all of the easy questions were completed

**Here the students were told to 1: don’t try to suppress anxious thoughts (at this point the white bear example was invoked to prove that suppression doesn’t actually work), 2: not pass judgement on whether or not their anxious thoughts were justified (eg: ‘Am I having this thought because I actually am dumb?’ This equates to realising that the “White Bear Intelligence Test” is in fact not an intelligence test), 3: see anxious thoughts are something that are going to naturally pass through a person’s mind, and that they don’t have to do anything about them. From time to time, everyone thinks about white bears!

I’m keen to emphasise here that this intervention was only 10 minutes long, and immediately prior to the test, this makes the results even more interesting!

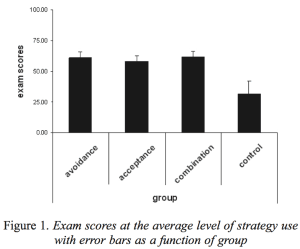

Of course it was checked that there wasn’t any bias present in the groups prior to the training (ie: all groups had a similar distribution of ‘anxious’ and ‘not-so-anxious-ish’ people) and all that jazz, and in the end, this is what came out in the wash (see right, from pg. 423)

All 3 treatment groups did (statistically) significantly better than the control group!

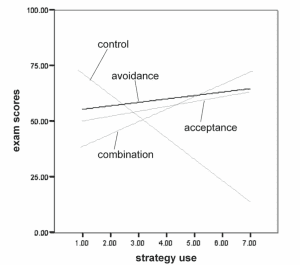

The authors also looked at test scores as a function of how frequently test strategy was employed. This was measured by asking the participants to rate, on a scale from 1 to 7, whether they used coping techniques (7 being very frequently). This revealed an interesting result.

Essentially, the more often the treatment participants employed the techniques, the more successful they were in the test (correlation). Conversely, more frequent use of techniques by the control group (techniques of their own choosing) was correlated with lower exam scores. This was likely because it was simply an indication that they were having more anxious thoughts, which were not being effectively dealt with and thus compromising their performance.

Essentially, the more often the treatment participants employed the techniques, the more successful they were in the test (correlation). Conversely, more frequent use of techniques by the control group (techniques of their own choosing) was correlated with lower exam scores. This was likely because it was simply an indication that they were having more anxious thoughts, which were not being effectively dealt with and thus compromising their performance.

Also interesting to note is that there was no statistically significant difference between the results of the 3 treatment groups. The authors suggested that this could have been due to a ceiling effect whereby maximum returns to technique were reached by either of the strategies used in isolation (acceptance or avoidance). Thus, using strategies in combination didn’t yield any significant improvements above the use of either of them individually.

So, in conclusion, you help your students to improve their test performance by letting them know that skipping hard questions and coming back to them later and by telling them that it’s ok and normal to have anxious thoughts. “When you have anxious thoughts you can just think to yourself ‘how interesting, an anxious thought, oh well, that’s normal’ and continue on with your test”. I’m amazed by how just a 10 minute intervention had statistically significant results!

I would be interested to see the effects of longer term acceptance strategy training, such as meditation, on an individual’s ability to deal with anxious thoughts. I’m personally really enjoying using the Headspace app at the moment to do daily meditation. And I do feel that an approach of ‘seeing my thoughts as passing cars on the road, there’s no need to get picked up and taken away by them, just watch them pass’ has really helped me to be more positive and let negative emotions go more easily since I started the training a few weeks ago 🙂

References:

Ashcraft, M. H., & Kirk, E. P. (2001). The Relationships among working memory, math anxiety, and performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130, 224–237.

Senay, I., Cetinkaya, M. and Usak, M. (2012). Accepting test-anxiety-related thoughts increases academic performance among undergraduate students. Psihologija, 45(4), pp.417–432.