Spaced repetition, and the software Anki in particularly, has changed my life. For many years I lamented my inability to recall things that I’d read, the names of people I’d met, or other information that I felt was important. Spaced repetition software provided me with a structured way to file and retain important information both externally in a database, and internally in my brain. Anki is so valuable to me that I even listed it as one of the five things that I couldn’t live without on my online dating profile (worked as a great pro-nerd filter!)

In short, Anki is a software that enables users to make digital flashcards, and then returns those flashcards to them on an algorithmically optimised schedule in an attempt to ensure maximum retention of information in minimum time spent studying.

But Anki has limitations. One of the key things we know about retrieval practice is that it can only reinforce the snapshot of memory that already exists in long term memory, it can’t refine it. This means that Anki isn’t good for learning, it’s only good for remembering. As one of the world’s foremost spaced repetition gurus, Piotr Wozniak writes, ‘Learn before you memorise’.

For the seven or so years that I’ve been using Anki to date (it’s currently May 2020), this has meant that there’s been a missing link in my information processing chain. Essentially, I’d read something, find an interesting bit, highlight it, and if I was disciplined enough, I’d return to it at some later point and turn it into an Anki card.

However, as mentioned, we shouldn’t try to memorise before we’ve truly learnt it, and for new and complex ideas, a single reading usually isn’t enough to really process the idea at a deep level. That processing should occur before creating the snapshot of the memory in the form of an Anki card, and the Anki card should simply crystallise the pre-formed concept for safe keeping in long term memory.

This lack of a good intermediary process between initial reading and Anki card creation remained a persistent problem for me. And it wasn’t until I interviewed George Zonnios for the ERRR podcast, and discovered his software Dendro, that I found a solution!*

The solution is incremental reading. Incremental reading is a process whereby you extract the essence of a piece of text over time, changing it, putting it into your own words, and refining it to form a rich memory. As you continue, you condense that rich memory down, and distill it into a sentence, perfectly prepared for spaced repetition.

It’s hard to explain this process without seeing it in action, so here’s a short video introduction to incremental reading with Dendro.

*I’ve since started working with George on Dendro! There’s another similar software, Supermemo that has similar functionalities that you may also like to experiment with, but I can’t user Supermemo as it isn’t compatible with macs.

I now do the majority of my reading through Dendro. I upload articles that I want to read, pdfs of books, and also have some hacks and techniques to integrate it with my kindle reading, youtube/TED talk watching, and reading of hard copy books too.

Dendro is still in the development phase, but it’s very functional and it’s already changed the way I read and interact with information. Another major problem in my info processing chain that Dendro has helped me to overcome is my note taking, whether it be from a meeting, a conference presentation, or a podcast. Originally I’d make notes in Word docs, but I’d never revisit them. Then I made them in google docs, but I’d never revisit them. Then I made them in Evernote, but I’d never revisit them. And most recently I’ve been making them in emails and emailing them to myself. This final method was a little better, but it still seemed a massive chore to revisit the copious notes I’d made at a conference, follow up all the links, and try to make Anki cards out of the good bits (often not deeply learning before memorising).

Now I just make my notes directly into Dendro and I’m supported to incrementally digest them over time. I don’t feel any rush to do so, and the software’s algorithm guides me to visit, and revisit the notes over time. It’s truly a joy!

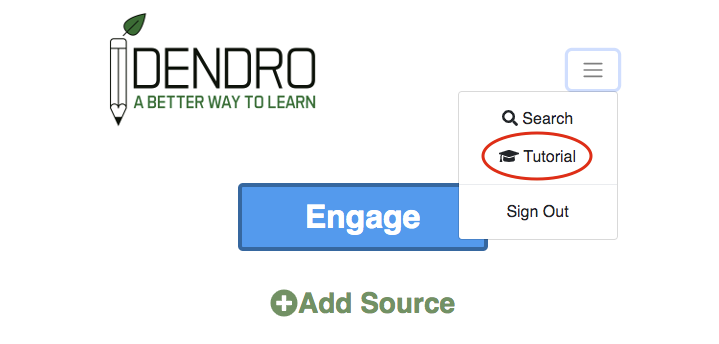

cIf you’d like to have a go at using Dendro, you can sign up for a free account here. After you’ve signed up, you can access the tutorials from the main drop down menu top right.

Further reading: If you’d like to read a much more detailed outline of the how Dendro’s design is backed up by learning science, you can check out the ‘Dendro Manifesto‘ too. You may also like to check out how I use Dendro in conjunction with hard copy books here.

Good luck exploring Dendro, and please feel free to email me, or tweet at me any time with questions, comments, thoughts, or reflections.