Summary: To suggest that a student listening to music at the same time as trying to focus on their work is an example of the split-attention effect is incorrect! In’ this blog post I’ll briefly outline what the split-attention effect is, I’ll then share what it isn’t, and conclude with a comment from John Sweller on this misconception.

…

It has been incredibly exciting to see more and more teachers referring to the all important Cognitive Load Theory over the past few years. The way that I define it, ‘Cognitive Load Theory is a collection of instructional recommendations based upon the science of how humans learn’, and it does a fantastic job of describing the way that our human memory system works, and what that means for instructional design.

However, when ideas become more mainstream, things can sometimes get lost in translation. On the whole, I feel that CLT has maintained its integrity quite well throughout its popularisation, but there is a misconception that I’ve started to see creep in recently. I’ve heard three or four educators incorrectly refer to the ‘split-attention effect’ within schools over the past couple of months, I’ve seen it misrepresented on a school’s website, and also in a recently published education book.

The Split-attention effect: What it is

Here’s a bullet proof definition of the split-attention effect: ‘Information that must be combined should be placed together in space and time.’

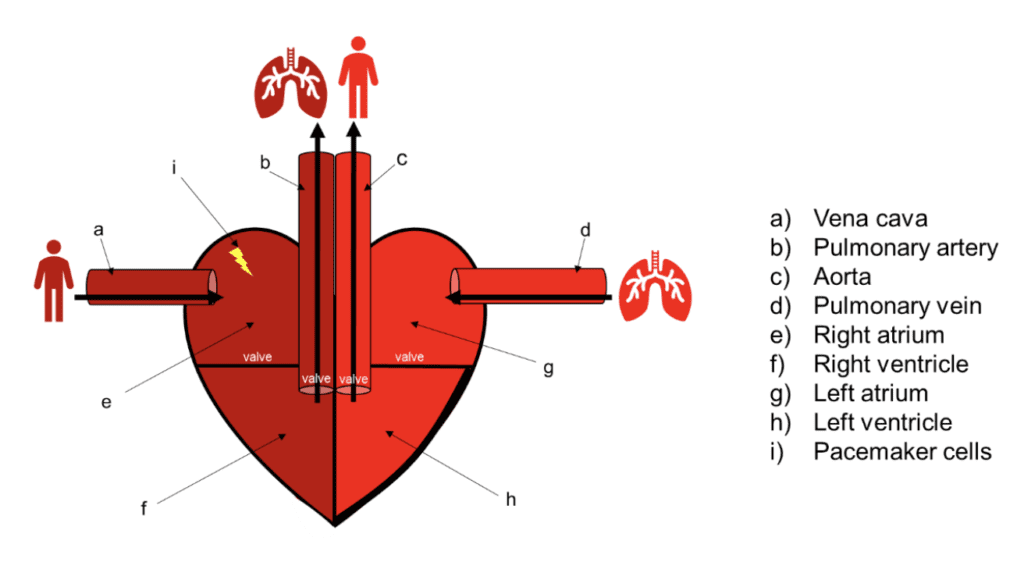

During learning, students are often required to integrate multiple pieces of information in order to understand the full picture of the learning task. When that to-be-integrated information is not placed together in space and time, students have to hold one part of the information in working memory, transfer it through space, then integrate it with the other piece to form a complete picture. Let me give you an example. Consider the following image (which I found on the teach, reflect, share website).

If we want students to learn the components of the heart from this above diagram, they need to go to the list, identify that heart component ‘a’ is the Vena cava, hold that word ‘Vena cava’ in mind, then look back across to the heart diagram and find the part that’s labelled ‘a’ on the left-hand side of the image (or vice versa, start at the diagram then go to the labels). This process is more cognitively demanding than it needs to be, because this same information can be presented to students in a way that requires them to hold less in their working memory. Said another way, we could integrate the image and the labels to reduce extraneous cognitive load, as follows:

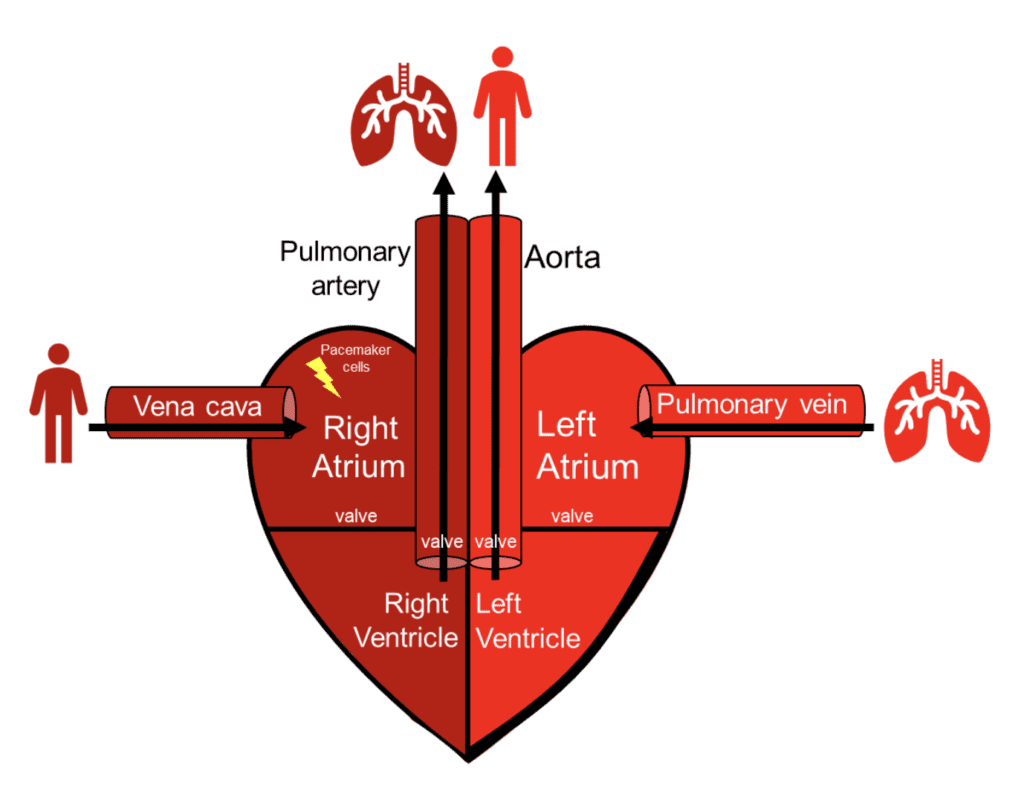

In this format, students can simply look directly at the image, and see exactly what each part of the heart is called. Their attention hasn’t been split between the image and the labels, because the image and labels have been integrated for them. This streamlines the learning task for the students.

Another example that many of us would be familiar with is found in papers and reports. Often a figure (graph or table) is presented on one page, then the description may be overleaf. In such situations, it can be very difficult to interpret the description of the figure, because we have to hold the figure in mind (our working memory) whilst we flip back or forward the page to integrate it with its description (or vice versa, hold description in mind whilst we go back to the figure). As document writers, we should ensure that figures and their matching descriptions aren’t split by a page break. As readers, we can get around this by taking a snippet, screenshot, or photocopy (if in hardcopy form) of the figure, and placing that on the same screen or desk so that we can see both the description, and the figure at the same time. This doesn’t eliminate split-attention, but it does reduce it.

Hot tip: When reading a document in Microsoft Word and checking references, there’s a ‘split screen’ button that you can use that splits the screen and enables you to independently scroll the top and bottom half of the viewing window independently. I use this frequently to reduce split attention, you might like to try it! (pictured below).

The Split-attention effect: What it isn’t

Here’s one misrepresentation of the split-attention effect that I saw recently:

‘Whilst students are working, don’t disturb them…Don’t talk about homework, or what we are going to do in the rest of the lesson, or why we are doing this quiz or whatever…. If students are attending to one thing, doing anything that causes them to focus on something else leads to worse learning (due to the split attention effect). ‘

Here’s another:

‘Managing distractions to avoid the split attention effect, such as listening to lyrical music and checking messages while studying. ‘

Don’t get me wrong. In both cases, this is excellent advice. And it’s also definitely true that in both cases, students’ attention is split (in a colloquial sense) between the task that they should be focussing upon (their work) and a distraction (either teacher talk, or music). However, the fact that their attention is split doesn’t mean that it’s an example of the split-attention effect.

As mentioned in the introduction, I’ve also heard three or four teachers say similar things within schools. That is, suggest that managing distractions is key because it reduces split-attention. That’s why I felt it important to write this blog post, to try to correct this misconception before it becomes too widespread.

What does John Sweller Think?

Before I wrote this blog,, I shared the above quotes with John Sweller and asked for a comment. John wrote the following in response to my suggestion that the split-attention effect has been misrepresented:

‘Yes, they have confused the split attention effect with the redundancy effect. Cognitive load theory classifies the activities they described as being redundant. They are correct when they say that the inclusion of such materials and information depresses learning but of course, it is not due to split attention.‘

So, what should we be saying instead?

As Sweller highlights above, students listening to music at the same time as working, or teachers talking when students are trying to focus on their work, are examples of redundancy. Within Cognitive Load Theory in Action, I summarise the redundancy effect as, ‘Eliminate unnecessary information and do not replicate necessary information.’ In these examples, the teacher speaking, and the lyrical music, are not necessary for the current learning task (though they both may be relevant to some future learning task, but they aren’t the focus right now), so they’re redundant, and should be eliminated.

We could therefore amend the above two excerpts as follows:

‘Whilst students are working, don’t disturb them…Don’t talk about homework, or what we are going to do in the rest of the lesson, or why we are doing this quiz or whatever…. If students are attending to one thing, doing anything that causes them to focus on something else leads to worse learning (due to the redundancy effect). ‘

‘Managing distractions to avoid the redundancy effect, such as listening to lyrical music and checking messages while studying. ‘

…

The advice from these authors is excellent, and should definitely be heeded. It’s crucial for us to manage redundant distractions in the classroom so that students can focus on the key learning taking place. Let’s just ensure that, as a profession, we’re referring to the management of distractions as reducing redundancy, not as reducing split-attention.

One Reply to “Are you using ‘Split-attention Effect’ incorrectly?”

Comments are closed.