What knowledge, truth-seeking, mental models, and automation have to do with expertise

In my quest for a successful and fulfilling life, there’s been one approach that’s served me better than any other: ‘Find an expert and do what they do.’

From relationships, to teaching, podcasting, rock climbing, leadership, or even cornhole, I’m yet to find a domain of expertise in which this approach hasn’t helped me to make better progress.

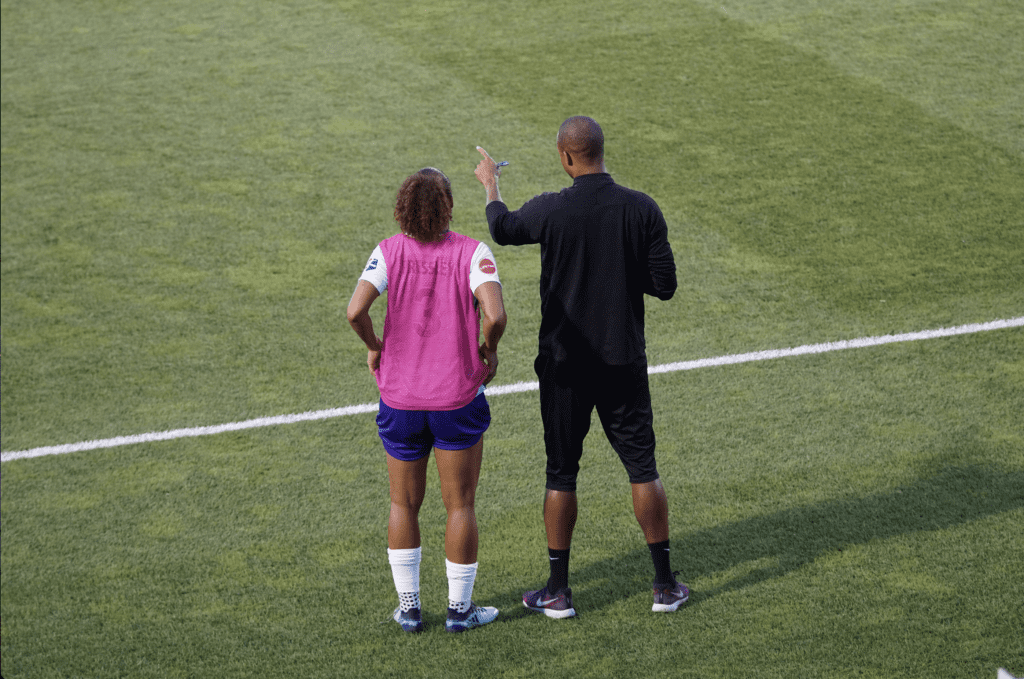

Thinking more about teacher development has pushed me to consider this approach from both angles. Under ideal situations, what does it look like for an expert, and a novice, to work together to advance the knowledge and expertise of both in tandem?

In pondering this important question, I’ve come up with three tenets that I believe map out how a novice and an expert can come together to promote rapid and sustainable improvement. Here they are:

- Novices make the most rapid progress when they work with credible experts

- Credible experts are those who are knowledgeable and truth-seeking

- Credible experts become expert coaches when they help novices to acquire their mental models and automate their practices

I’ll briefly touch on each in turn.

Novices make the most rapid progress when they work with credible experts

This idea is a generalisation of my approach stated above, ‘Find an expert and do what they do.’

If we accept the role of knowledge in expertise, then it is self-evident that providing a novice with access to the knowledge structures and collective wisdom of an expert is the fastest way to enable progress.

Sweller puts it well in the following:

‘In any biologically secondary area, we can expect the major, possibly sole difference between novices and experts to consist of differential knowledge held in long-term memory.’

John Sweller et al. (2011) Cognitive Load Theory. p. 21

Credible experts are those who are knowledgeable and truth-seeking

But how do we know if we’re working with a credible expert?

David Didau points us in a useful direction in his book Intelligent Accountability. Didau suggests that ‘accountability is most likely to lead to positive behaviours and improved performance’ when those to whom we’re being held acountable are knowledgeable and truth-seeking*

We can tell if our coach, head of department, doctor, trainer, or teacher is knowledgable if they can effectively identify what you can do to improve, how you can make such improvements, and why such an approach will be effective.

We can tell if they’re truth-seeking if they’re clearly open to and seeking input, and not jumping to conclusions or pushing a specific agenda.

In most cases, these two characteristics go hand in hand. If a so-called expert continually draws from the same bag of tricks or recommends the same remedy regardless of the ailment, then they either have a very limited back of tricks, or they’re getting a kickback for dishing out the remedy.

Thus, to be a credible expert, we must listen and seek the truth (aka: We must truly wonder, not just pretend we’re wondering), we must be knowledgable, and we must base any advice or recommendations that we provide on a synthesis of the two.

Credible experts become expert coaches when they help novices to acquire their mental models and automate their practices

One of the dangers of using the approach, ‘Find an expert and do what they do’ is that we end up in mimicry.

Mimicry is when the novice does what the expert does, but they don’t know why they do it. The result is a fragile replication of the expert’s actions that is perilously at risk of mis-application (for more on mechanisms, routine and adaptive expertise, and lethal mutations, see Chapter 8 of Tools for Teachers).

The only way around this is when to credible expert actively works to imbue the novice with their mental models, and provide them with the rehearsal required to automate their practices.

Solid mental models represent well-structured and robust, interconnected knowledge that allows the budding expert to adapt what they’ve learnt to a large range of scenarios that they may face in future.

An automation of practices achieves two ends. Firstly, it ensures that any gains made begin to become habit, which makes these changes sustainable for the longer-term. Secondly, by moving from conscious competence to automated competence, the budding expert frees up cognitive resources to work on the next stepping stone towards expertise.

This process is ideally scaffolded by the credible expert (who, in so doing, becomes an expert coach), but it can also be driven by the novice. When a novice recognises that they need to move beyond mimicry to deep understanding and automation, they can demand or self-initiate the kind of generative learning and deliberate practice that is most likely to result in their own acquisition of true expertise.

…

What are you trying to get better at currently? Could you find yourself a credible expert?

Keep your eyes peeled for the next EdThread in which I’ll apply some of the insights from this post to the thorny topic of ‘Choice’ in Instructional Coaching and teacher development!

*This is one of three conditions that Didau lays out on pg. 82 of Intelligent Accountability. The specific terminology used in Intelligent Accountability is ‘well informed and interested in accuracy’, but I have used ‘Knowledgable and truth-seeking’ herein based upon Didau’s video presentation where he used this terminology instead, which I feel is more straightforward and clear.