Let’s play spot the difference. Here are two very similar questions.

- Your car is having some trouble and requires $150 to be fixed. You can pay in full, take a loan, or take a chance to forego the service at the moment… How would you go about making this decision?

- Your car is having some trouble and requires $1500 to be fixed. You can pay in full, take a loan, or take a chance to forego the service at the moment… How would you go about making this decision?

These two subtly different questions are the ones that Mani, Mullainathan, Shafir, and Zhao took to a New Jersey mall in 2013. Their goal? To examine the interaction between poverty and cognition.

The hypothesis was that for someone doing ok financially (‘rich’), the $150 vs. $1500 condition wouldn’t make a massive difference. However, for those experiencing financial hardship (‘poor’), $150 to fix your car would be manageable, whereas $1500 could be a real road block (pardon the pun).

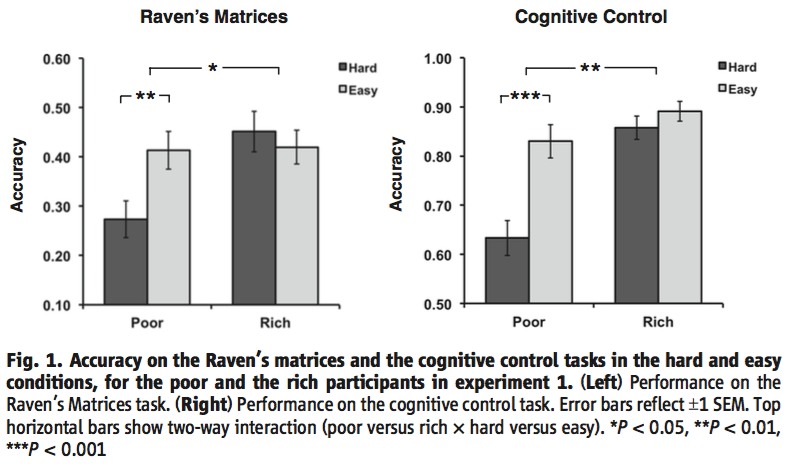

What the experimenters were keen to work out was whether such a difference would impede individuals’ cognitive function, and whether the impacts would differentially impact rich and poor participants. They posed question 1 to some participants, and question 2 to others, then followed this up a short time later by measuring cognitive function through Raven’s Progressive Matrices and a spacial compatibility test (pressing different sides of a screen based upon various visual simuli).

The results?

Those who were poor and told they’d have to pay $1500 to solve their hypothetical car problem performed significantly worse on both measures of cognitive function when compared to all other groups (see image below). This suggests that when those who are poor are primed to think about potential financial hardship, their cognitive function is impeded (if this seems like an overly obvious finding, please read on).

Mani and colleagues took it further and provided financial incentives for participants’ performance on the cognition tasks. Despite the fact that such financial incentives probably meant more to the poor participants, the findings still remained significantly different for the ‘poor+$1500 bungle’ condition.

Now, this is all very interesting, but it’s a short term impact. It was time to explore these impacts over longer timeframes, and to take the experiment further afield.

Taking things further afield

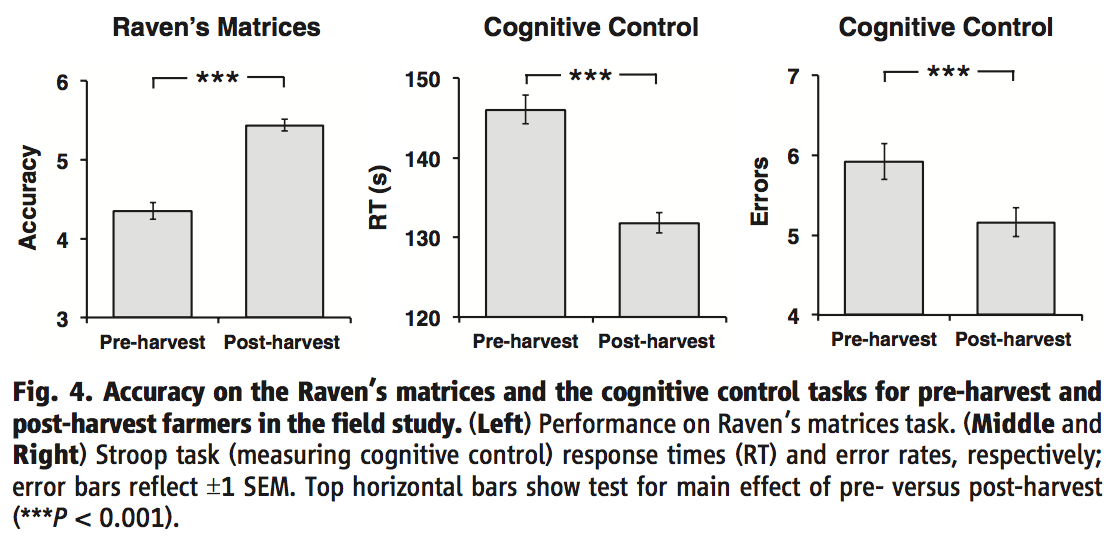

Mani and the team went to the fields of 464 sugarcane farmers in Tamil Nadu, India. They wanted to examine the pre-and post-harvest cognitive performance of these farmers to look for any financial hardship/cognition interaction.

Prior to harvest, these farmers exhibited significant financial hardship, they pawned items at a rate of 78% vs. 4% (pre vs. post-harvest), were more likely to have loans (99% vs. 13%), and were more likely to admit having trouble coping with bills in the last 15 days too.

The research team again administered cognitive assessments (this time Raven’s matrices and a numerical version of the Stroop test).

The findings were consistent with the first study. Significant differences existed between pre-and post harvest performance, as pictured below. Furthermore, this wasn’t due to learning, as the experimenters controlled for this. Also, it wasn’t due to physical exertion pre-harvest, or anxiety about crop yields, as most of these farmers hired external labour, and harvests can be readily estimated several months prior to actual harvest.

In previous studies the authors also controlled for factors such as nutrition, and physical manifestations of stress. The results still held.

Mani and colleagues suggest that this reduction in performance due to financial stress is roughly equivalent to a drop of about 13 IQ points.

The authors conclude (pg. 979)

Taken together, the two sets of studies—in the New Jersey mall and the Indian fields—illustrate how challenging financial conditions, which are endemic to poverty, can result in diminished cognitive capacity.

So what?

Reading about these studies prompted in me a greater appreciation for the challenges faced by those in poverty, especially when thinking about the challenges of ‘closing the gap’ between more and less advantaged pupils at school. These findings suggest that poverty doesn’t just mean dealing with a lack of physical resources, but also a diminution of cognitive resources.

But it also prompts more immediate action for those working directly with students living in poverty. In their conclusion, the authors suggest that, in the same way that we’re wary of imposing monetary taxes on the poor, so should we be careful imposing cognitive taxes upon them. Instead of engaging students in lengthy conversations about the importance of homework, or prompting them to write detailed plans about how they’re going to manage their time (both cognitively demanding tasks), perhaps we should be focussing on simple interventions that aim to reduce the cognitive burden, such as scheduling text message reminders to help them stay on top of their studies.

Finally, it’s interesting to consider these findings in light of recent work on cognitive load theory that suggests that working memory can exhibit depletion effects (Chen, Castro-Alonso, Paas & Sweller, 2018). It appears as thought prolonged mental effort can result in reduced working memory capacity in the short term following such exertion. Relatedly, the work in this poverty and cognition paper suggests that poverty taxes cognition by means of ‘attentional capture’. I’d love to see more work in this space in order for us to better understand and support the students with whom we work.

Shout out

For the past three years or so I’ve been meaning to blog about this poverty and cognition article. However, due to a poverty of another kind (time), it somehow hasn’t happened. Last week I came across an excellent post from Iesha Small (@ieshasmall) which prompted me to think about this issue again. Iesha’s piece summarises a recent report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, How poverty affects people’s decision making processes, with Iesha presenting some of the key findings and weaving in personal reflections along the way. Her piece is entitled What middle class teachers need to know about their working class pupils in poverty. If you’re a teacher who works with disadvantaged students, I suggest you check it out. Here’s a snippet:

I’ve been educated and worked in middle class mostly white environments my whole life but I come from a Black working class one and some discussions that I have heard and been part of in my position as a teacher and leader in schools have left me very uncomfortable. There is often an assumption that we need to save people from themselves (both the children and their parents). Working class people are infantilised and automatically assumed inferior. Often in a well-meaning way but that’s definitely the subtext. That’s before we even get into the classist nature of many schools themselves.